Applying Halakhic Ethics to Twenty-First Century Science

BY MARC DWECK

The rapid pace of scientific advancement has fundamentally transformed our world, presenting novel ethical challenges that demand careful consideration. As humanity pushes the boundaries of what’s possible through genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and groundbreaking medical procedures, it is paramount to find ways to apply timeless ethical principles to these unprecedented scenarios. Halakha (Jewish law) exemplifies how ancient wisdom can successfully adapt to and guide us through modern technological developments.

While many believe that ancient principles should be abandoned in favor of modern understanding, we—as Jews, a people of an ancient religion—fundamentally disagree. Our tradition demonstrates that timeless wisdom can provide crucial guidance in emerging contexts. Moreover, halakha’s ability to evolve has always been tied to its sophisticated approach to emerging challenges, which can provide additional guidance for these ever-evolving technological times.

High school students now regularly engage with technologies that were once confined to advanced research laboratories—from genome sequencing to artificial intelligence programming. In many Jewish Day Schools, this scientific progress has been met with equally rigorous analysis in halakha. In my own experience, high school halakha curricula now combine traditional Jewish legal principles with contemporary scientific challenges, exploring complex topics like abortion, genetic testing, and the determination of death through a sophisticated halakhic lens. As science continues to venture into uncharted territories, these dynamic yet deeply rooted principles offer crucial insights for addressing the complex moral questions of our time.

A prime example of how students engage with these principles can be found in the study of medical ethics, particularly organ donation and transplantation. In a careful analysis of organ donation through a halakhic lens, students learn how to apply ancient wisdom to medical innovations. The following exploration of Jewish law’s approach to organ donation illustrates the kind of sophisticated ethical reasoning that I’ve encountered in my course work, particularly in a class titled “Health and Halacha: Sources and Contemporary Conversations,” taught by Rabbi Asher Bush.

Organ transplantation, while revolutionary in saving millions of lives, presents complex ethical challenges within Jewish law. The central question emerges: does the Jewish obligation to preserve life extend to mandatory living organ donation—a process where a healthy individual would donate a vital organ to save another person’s life? It is a halakhic precept and a tenant of common human decency to do anything in one’s power to save another’s life. But the question becomes more nuanced when we consider the potential risks involved in organ donation.

The foundational ruling here comes from the Radbaz (Rabbi David ben Zimra) in the early 1500s. Addressing a scenario where a tyrant ruler threatened to kill one person unless another person allowed their limb to be amputated, he determined that while making such a sacrifice is commendable, it is not obligatory. He notably characterized those who would risk their lives through such sacrifice as “pious, but foolish.” This ruling provides the framework for modern organ donation ethics, establishing it as a praiseworthy but non-mandatory act when significant risk exists.

Though this applies to donations of organs (where there is substantial risk), other minimally invasive procedures such as blood and bone marrow donation—where risk is virtually nonexistent—raise other concerns. Is one obligated to donate if it will cause pain or substantial discomfort?

Rashi, commenting on a Gemara in Sanhedrin, rules that one must do anything short of putting themself in danger to save someone in peril, including, but not limited to, enduring physical or monetary strain. Contemporary Rabbis, led by Rav Hershel Schachter, have interpreted this ruling to apply only to a case where someone is in immediate danger and will die without the transplant. Therefore, one is only required to donate blood when they know it is needed to perform a lifesaving procedure. Similarly, though one is not required to get tested to see if they are a match for bone marrow donation, once they decide to do so they are required to donate.

The ethics surrounding organ donation have become more complex as the methods for determining brain death have evolved. Since the inception of the field, organ donation has been governed, for Jew and non-Jew alike, via the Dead Donor Rule, which prohibits the donation of vital, non-regenerating organs from living donors.

The Dead Donor Rule faces reexamination as medical technology enables maintenance of bodily functions after complete brain failure. Modern technology such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machines can now sustain heartbeat, circulation, and other physical functions even when the brain has irreversibly ceased all activity, creating a new category of potential donors whose status as “living” or “dead” remains ethically contested. The question of whether brain death constitutes true death—and whether it should determine a person’s eligibility for organ donation—remains a contentious issue among contemporary scholars, including within the Jewish community, where the debate continues to evolve.

Jewish scholars universally accept the principle behind the Dead Donor Rule, preventing one from sacrificing themself to save another, with Rashi famously declaring “Who knows whose blood is redder?” (Sanhedrin 64a). However, there exists no unified position among scholars on the status of brain death. While traditional sources reference respiration, heartbeat, and movement as determinants of death, these criteria reflect historical biological understanding rather than moral or halakhic principles.

The Rambam’s commentary on post-mortem movement provides significant support for accepting brain death as true death. He argues that physical movement indicates life only when coordinated by a central source: the brain. Modern scholars have extended this reasoning to brain death, equating physiological “decapitation” (the severance of brain-body connection) with physical decapitation. Still, many have reservations adopting this approach, so the issue remains an ongoing debate.

This rigorous engagement between halakha and the modern medical landscape demonstrates the dynamic capacity of Jewish law to address unprecedented technological advances, establishing vital precedents that will shape religious and ethical responses for generations to come—from artificially developed organs to future biomedical innovations we have yet to imagine.

Suggested Reading

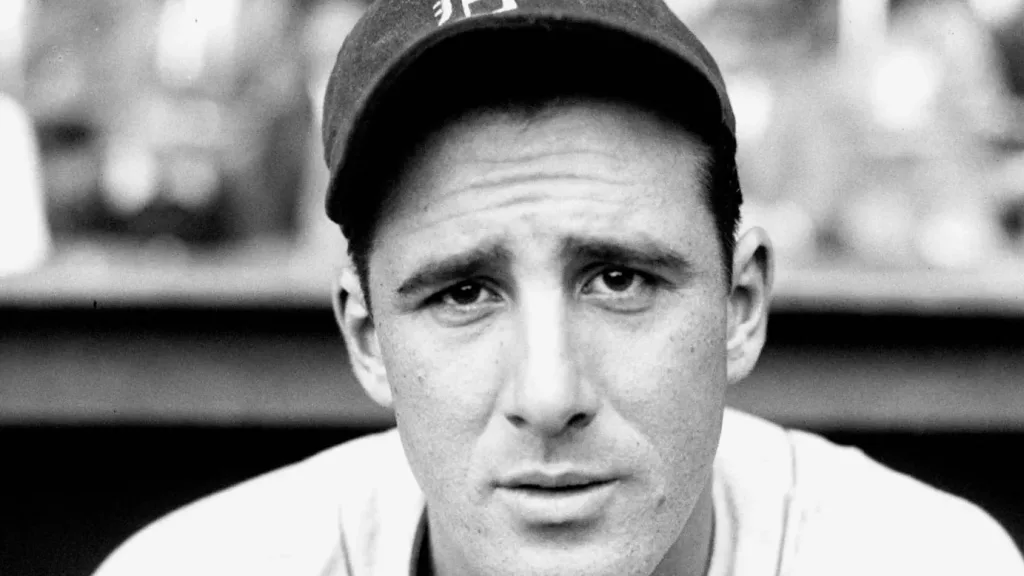

An American Jewish Folk Hero

A striking fact about modern Zionism is that its founder, Theodor Herzl, dedicated his life to Jewish statehood despite originally caring little for Jewishness. At one point, he even advocated…

Dance in the Jewish Tradition: From the Torah to the Twenty-First Century

BY GABRIELLA FRIEDMAN The invigorating passion and animation that an ensemble of dancers embodies onstage is an awe-inspiring experience that most residents of the New York area, myself included, have…

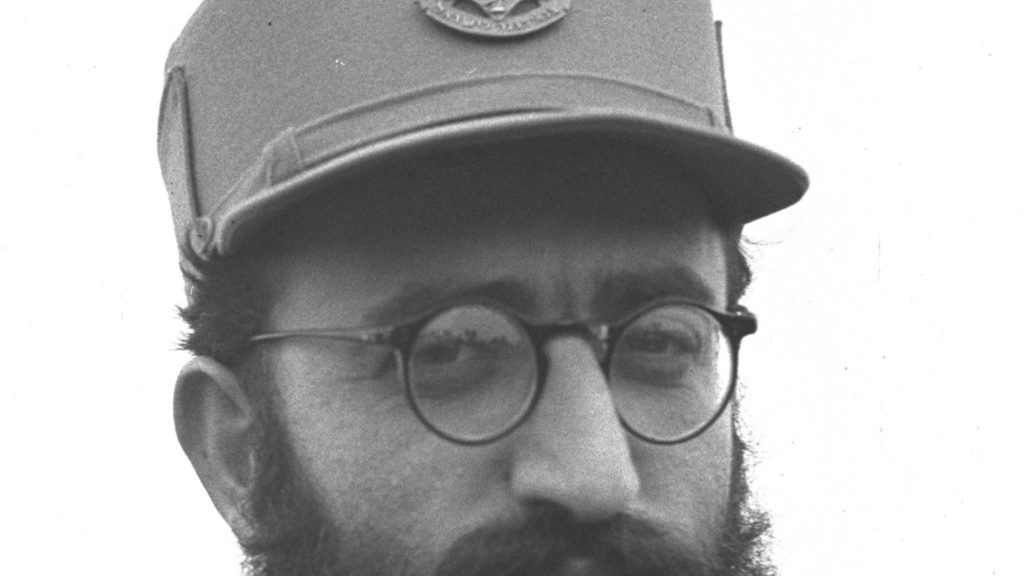

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

Vast as the Stars and Sand

BY ELISHAMA SCHWARTZ Some of us lounge with verdant backyards and homey porchesOthers are squeezed by neighboring skyscrapers and smokeButEither waysometime in winter,I’ll be comforted by the beam of the…