Zionism Is Not Just Politics

BY ADIEL RAMIREZ

In January 2024, Americans witnessed a series of highly publicized congressional hearings featuring testimony from the presidents of MIT, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania on the issue of campus antisemitism. Their testimonies were uniformly evasive, and the uproar that followed led to the resignations of Harvard President Claudine Gay and University of Pennsylvania President Liz Magill. The episode was deeply embarrassing for these supposedly elite institutions and left their Jewish students feeling more intensely alienated than ever.

In the aftermath of these disastrous hearings, the pro-Palestinian camp doubled down on a common talking point: antisemitism is wrong, but Zionism, a political ideology, is a legitimate target for protest and delegitimization. Not only is this framing deeply hostile to Jewish students (as emphasized by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism), it serves as a rejection of a fundamental part of Jewish identity. Zionism is not merely a political stance that one takes; it’s an expression of Jewish historical memory, spiritual longing, culture, and continuity.

History shows us time and time again that Zionism has always been a crucial pillar of Jewish heritage. Zionism is not a sterile political concept; the Jewish longing for Israel, the Jewish national homeland, has permeated diasporic Jewish culture since its beginning. Many passages in the Navi refer to Hashem’s promise of the return of diaspora Jews to the land of Israel. Many psalms include a reference to the land or the constant yearning for it, most notably psalm 137:

אִֽם־אֶשְׁכָּחֵ֥ךְ יְֽרוּשָׁלָ֗͏ִם תִּשְׁכַּ֥ח יְמִינִֽי \ תִּדְבַּֽק־לְשׁוֹנִ֨י ׀ לְחִכִּי֮ אִם־לֹ֢א אֶ֫זְכְּרֵ֥כִי אִם־לֹ֣א אַ֭עֲלֶה אֶת־יְרוּשָׁלַ֑͏ִם עַ֝֗ל רֹ֣אשׁ שִׂמְחָתִֽי׃

If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right-hand wither; / let my tongue stick to my palate if I cease to think of you, if I do not keep Jerusalem in memory even at my happiest hour.

This is not simply a bible verse; it appears in Jewish prayers, songs, poetry and even contemporary art. In a similar vein, the Pesach seder, celebrated by Jews of all stripes around the world, concludes with a climactic call heralding “Next year in Jerusalem, rebuilt!” The 12th century poet Judah Halevi wrote poems about the desperate longing he felt for Israel and his inability to enjoy the pleasures of foreign lands. Centuries later, the 19th century poem that would become Israel’s national anthem (“Tikvatenu”) evokes this same longing:

:כֹּל עוֹד בַּלֵּבָב פְּנִימָה \ נֶפֶשׁ יְהוּדִי הוֹמִיָּה \ וּלְפַאֲתֵי מִזְרָח קָדִימָה \ עַיִן לְצִיּוֹן צוֹפִיָּה

As long as in the heart, within / A Jewish soul still yearns / And onward, towards the ends of the east / An eye still yearns toward Zion.

More recently, the Prayer for the Welfare of the State of Israel (“Avinu Shebashamyim”) and the Prayer for the Well-Being of the Israel Defense Forces has been incorporated into mainstream Jewish prayer services and communal ceremonies since the state was founded in 1948.

This spiritual, cultural, and literary longing for the land of Israel has uniquely manifested itself in the modern community of American Jews. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Zionism was a divisive issue within the Jewish American community. Many Polish and Eastern European Jews – recently escaped from pogroms and antisemitic governments – believed in Zionism as a matter of safety. But some assimilated Jewish immigrants to the United States hoped to avoid uncomfortable questions of Jewish loyalty and were disinterested and even hostile towards the Zionist movement. It was prominent Jews like Justice Louis D. Brandeis who helped convince many American Jews of the importance of Zionism and of its compatibility with American values. Brandeis often said, “To be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.” Many heeded his call; by 1917, the Zionist Organization of America included more than 200,000 members, funding many Zionist endeavors in Eastern Europe at the time.

In the last century, Zionist music, rituals, and art have grown in prevalence across American-Jewish institutions. Many songs sung at Ramah, the hugely popular conservative Jewish camp organization, have Zionist themes and Israeli origins, including the song “Eretz Zavat Halav,” whose lyrics reference the biblical description of the land of Israel flowing with milk and honey. According to a 2020 Pew Research study, around 80% of American Jews say that caring about Israel is crucial to their Jewish identities, and 58% report that they feel an attachment to Israel, including Jews across the religious spectrum.

It should be no surprise then, that given the centrality of Zionism in the American-Jewish community, political organizations have also emerged to advocate for a strong American-Israeli partnership. AIPAC, the most notable of these organizations, was formed in 1954, and the majority of its members are Jewish. But the Jewish commitment to promoting Zionism is based first and foremost in a cultural and religious commitment to Israel.

Zionism and a longing for the land of Israel has been foundational to Judaism for millennia and continue to be for most Jewish Americans today. While critiques about Israeli politics or American aid have a definite place in intellectual debate, Zionism is not simply a policy position but a core element of Jewish identity and it deserves the same respect granted to other expressions of communal heritage.

Suggested Reading

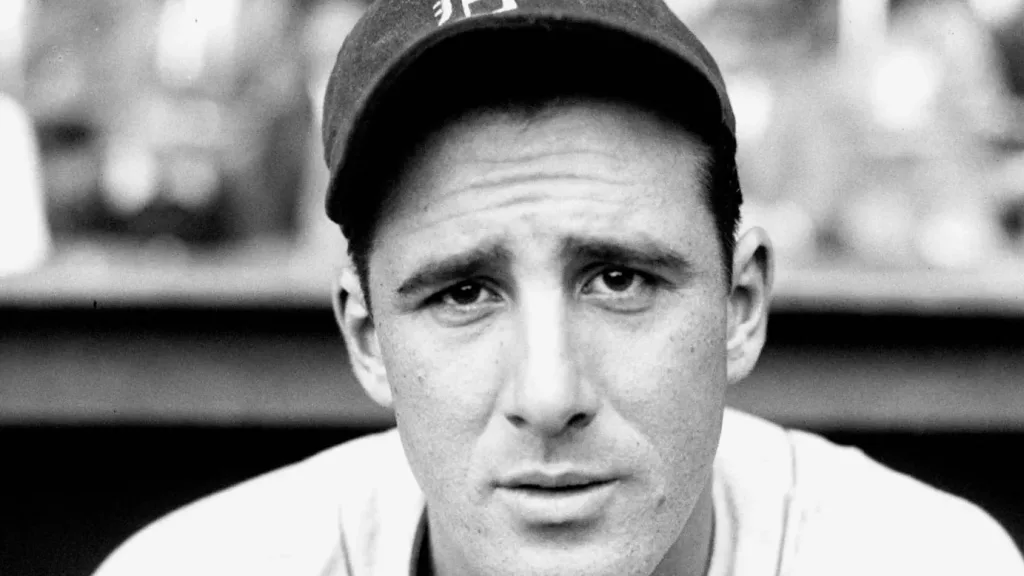

An American Jewish Folk Hero

A striking fact about modern Zionism is that its founder, Theodor Herzl, dedicated his life to Jewish statehood despite originally caring little for Jewishness. At one point, he even advocated…

Dance in the Jewish Tradition: From the Torah to the Twenty-First Century

BY GABRIELLA FRIEDMAN The invigorating passion and animation that an ensemble of dancers embodies onstage is an awe-inspiring experience that most residents of the New York area, myself included, have…

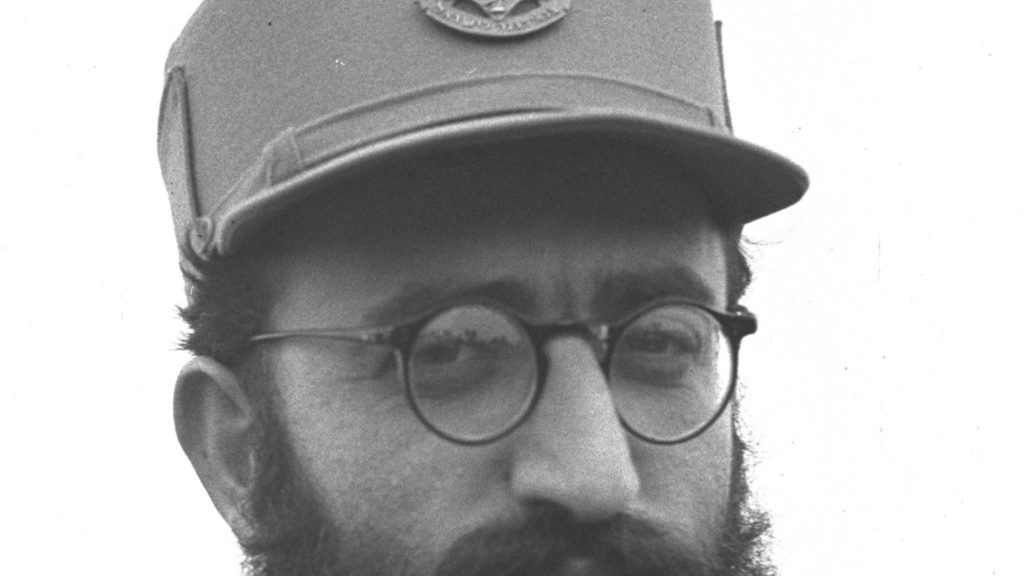

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

Vast as the Stars and Sand

BY ELISHAMA SCHWARTZ Some of us lounge with verdant backyards and homey porchesOthers are squeezed by neighboring skyscrapers and smokeButEither waysometime in winter,I’ll be comforted by the beam of the…