Good Fences Make Good Nations: A Shared Value in Both Judaism and Current American National Security

BY JACK YUNIS

According to most major polls, borders and immigration played one of the largest roles in President Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 elections. The concept of borders is an ancient one, and every war and treaty that establishes borders reinforces their role in defining a nation. This is precisely what President Trump meant when he famously said, “If you don’t have borders, then you don’t have a country.”

Borders have also played a significant role in religion, culture, and literature. Robert Frost, one of the great poets of the twentieth century, wrote that “Good fences make good neighbors.” Here is an example of the importance of borders in the Torah:

“Command the children of Israel, and say unto them: When ye come into the land of Canaan, this shall be the land that shall fall unto you for an inheritance, even the land of Canaan according to the borders thereof.” (Numbers 34:2)

Indeed, the renewed focus on the integrity of the borders of the United States is entirely consistent with the Jewish concept of a nation state. The Torah’s description of national borders is complex and links the duties of the individual Jew to collective national responsibilities. Starting from Abraham’s journey to the geographic boundaries set by God for the children of Israel, the Torah presents borders not just as physical markers but also as defining elements of national identity and responsibility.

Rabbi Menachem Leibtag notes that in God’s promises to Abraham, the land is described in very general terms, without any definite borders. For example, before Abraham famously departs his birthplace of Ur Kasdim, God tells him in Genesis 12:1, “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land which I will show you.” In a later prophecy in Genesis 13:15, God tells Abraham at Bet-El: “Raise your eyes and look out from where you are…for I give all the land which you see.” Later, the promise to Abraham is much more specific. At the Covenant Between the Parts (Brit bein ha Betarim), God tells Abraham: “To your offspring I assign this land, from the river of Egypt [i.e. the Nile] to the river, the river Euphrates” (Genesis 15:18-20).

This version of the borders of the promised land is expansive, stretching from modern-day Egypt to modern-day Iraq and would also have included most of modern-day Syria and Jordan. Shortly thereafter, just before God commands Abraham to perform brit milah, God describes the boundaries of the land of Israel quite differently:

“And I shall establish My covenant between Me and you, and your descendants…and I assign the land in which you sojourn to you and your offspring to come, all the land of Canaan,…and I shall be for you a God” (Genesis 17:7-8)

In this version, the borders of the promised land are much smaller. As with every instance of differing descriptions of the same entity in the Torah, the Torah is seeking to send a message, and in this case, about national borders and national obligations.

To understand the difference between these versions of the borders of the Land of Israel and the lessons this discrepancy teaches, it is important to review how the Torah develops the concept of what constitutes a nation, and what is required to be a citizen of a nation. In the text of the Covenant Between the Parts, God assures Abraham that his offspring will indeed conquer the Land, and indeed it will not happen until the distant future—four hundred years will pass, during which Abraham’s offspring will endure slavery in Egypt.

Only afterward will the children of Israel gain their independence and conquer the “promised land.” As Rabbi Leibtag notes, “this covenant reflects the historical/national aspect of Am Yisrael’s relationship with God, for it emphasizes that Avraham’s children will become a sovereign nation at the conclusion of a long historical process.” By contrast, the text describing the brit milah emphasizes a more personal relationship between God and His people, specifically, at the level of the individual or the citizen. This ever present connection between God and the children of Israel is not necessarily related to any form of national sovereignty and exists independent of a nation state.

From the story of Abraham and the covenants into which he entered with God, it is plain to see the centrality of national borders in Judaism. It is for this reason that organized Jewish opposition to traditional national borders, as seen through organizations like the HIAS (formerly Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), which is vociferously opposed to the President’s border policies, is so out of place, and moreover, that President Trump’s insistence on restoration of strictly enforced national borders is entirely consistent with Jewish ideals.

During his first term as president, Trump said, “I will fulfill my sacred obligation to protect our country and defend the United States of America.…We will defend our borders, we will defend our country.” The President’s choice of words is interesting and perhaps deliberately chosen to emphasize the connection between national borders and his obligation as president to protect the American people; in other words, this is his covenant with the American people.

Far from being an abstract concept or idea in which anyone is permitted to enter and exit at will, nations have always been defined by borders. Borders imply an obligation of the nation to its citizens and vice versa. One theme that Trump repeatedly emphasized during his first term as president as well as in his 2024 campaign is the fundamentally unjust nature of open borders, and importantly, for legal immigrants. In a November 2018 speech, he said,

“Mass, uncontrolled immigration is especially unfair to the many wonderful, law-abiding immigrants already living here who followed the rules and waited their turn. Some have been waiting for many years. Some have been waiting for a long time. They’ve done everything perfectly.…But they have to come in on a merit basis, and they will come in on a merit basis.”

Just as God established his covenant with Abraham, which heavily relied on His setting apart for Abraham a defined piece of land— the promised land—so too, the United States is a covenantal nation and has responsibilities to the citizens who adhere to the law of our nation. This requires just enforcement of clear laws against unchecked immigration.

Until recent years, clear policies towards border enforcement in the United States would not have been considered controversial. For example, in 1996 Democratic President Bill Clinton signed legislation further expanding border enforcement with the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, and famously stated, “We are a nation of immigrants …but we are also a nation of laws.” The revival of strong border policies is not only a return to more reasonable policies of the recent past, but also, entirely consistent with some of the ancient ideas that are described in the Torah.

Suggested Reading

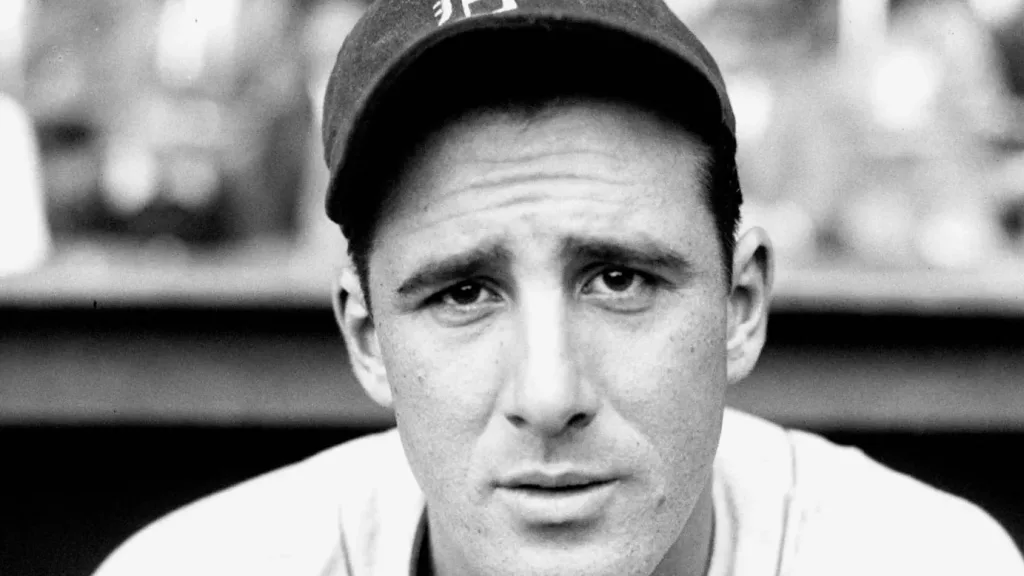

An American Jewish Folk Hero

A striking fact about modern Zionism is that its founder, Theodor Herzl, dedicated his life to Jewish statehood despite originally caring little for Jewishness. At one point, he even advocated…

Dance in the Jewish Tradition: From the Torah to the Twenty-First Century

BY GABRIELLA FRIEDMAN The invigorating passion and animation that an ensemble of dancers embodies onstage is an awe-inspiring experience that most residents of the New York area, myself included, have…

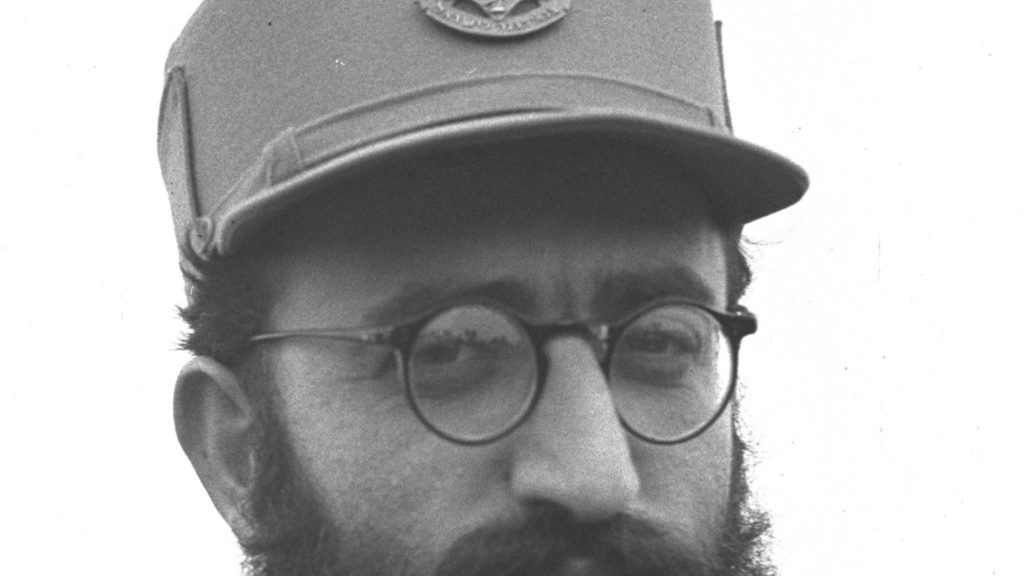

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

Vast as the Stars and Sand

BY ELISHAMA SCHWARTZ Some of us lounge with verdant backyards and homey porchesOthers are squeezed by neighboring skyscrapers and smokeButEither waysometime in winter,I’ll be comforted by the beam of the…