All About Mel

In an iconic moment of the 1967 film The Producers, scantily clad dancers dressed as Nazi sturmtruppen move into swastika formation and slowly rotate, surrounded by Third Reich banners and singers extolling the glory of the regime. It is the opening of the musical Springtime for Hitler, around which the plot of the The Producers ironically revolves. Joseph Levine, a producer of the film and head of Embassy Pictures, insisted the scene be cut. The director, Mel Brooks, promised it would be removed.

Brooks later noted, “This was the beginning of a pattern for me…lying to the studio at every turn. On every movie I’ve done since then, I’ve often lied when the studio objected to something by saying ‘It’s out!’” Of course, the shot remained in the movie, which became a hit and won Brooks an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

While Brooks’s irreverence informed his moviemaking, he often had a serious aim. As he writes in his 2021 autobiography All About Me!, “the way you bring down Hitler and his ideology is not by getting on a soapbox with him, but if you can reduce him to something laughable, you win.” His humor was also distinctly Jewish; Brooks’s career was forged in the so-called Borscht Belt, the Catskills summer resorts that catered to Jewish clientele. Brooks often appealed to higher ideals or causes through the seemingly absurd bits that defined his performances and films.

Brooks was born in 1926 in Williamsburg, New York, to a working-class Jewish family living in the tenements. His given name was Melvin Kaminsky; his father, Max Kaminsky, died when Brooks was only two years old. Brooks changed his professional name to avoid being confused with the well-known Borscht Belt trumpet player, Max Kaminsky. As he recalled in his autobiography, the name “would be a much better name than Melvin Kaminsky (which would be a good name for a professor of Russian literature).”

Brooks’s early work in the Catskills consisted of gigs as a pool tummler, amusing guests with comedic antics at resort swimming areas. The Catskills scene was a common starting point for Jewish comedians—Milton Berle, Joey Bishop, and Lenny Bruce all started their careers in the Borscht Belt. “But once the new business got under way,” writes Ruth Wisse in No Joke, “it was competitive as any other,” with Brooks willing to even risk his life to get a laugh. He once sank to the bottom of a pool with an alpaca coat filled with rocks during a tummler act.

After serving in the U.S. field artillery during World War II, Brooks worked for his friend, fellow comic actor and writer Sid Caesar, on the ground-breaking variety comedy series Your Show of Shows, which ran from 1950 through 1954. He went on to work on Ceasar’s next show, Caesar’s Hour, which ran from 1954-57. In the late 1950s, Brooks and his close friend and collaborator, Carl Reiner, began performing what became the famous “2000-Year-Old Man” comedic set; in 1961, an album titled 2000 Years with Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks sold over a million copies. At these shows, Brooks’ goal was the “ultimate punch line,” pushing a joke as far as it could go. Also in the 1960s, Brooks co-created the TV comedy show Get Smart, a send-up of James Bond films. As Brooks proclaimed in a Time interview, “I was sick of looking at all those nice sensible situation comedies. They were such distortions of life… I wanted to do a crazy, unreal comic-strip kind of thing about something besides a family. No one had ever done a show about an idiot before. I decided to be the first.”

In a way, Get Smart might have served as a precursor to The Producers—both shows thoroughly skewered larger-than-life figures that people took seriously. The idea of a satirical film about Hitler, however, was a tough sell. Brooks finally found an independent distributor who released it as a specialized art film, and it went on to become a smash underground hit on the college circuit and achieve critical claim—and, eventually, an Oscar. In the 1970s, Brooks adapted The Producers into a Broadway musical, which garnered an unprecedented 12 Tony Awards.

The Producers was a critical success, but Brooks had yet to capture the attention of America with a blockbuster. That changed in 1974, when Mel Brooks debuted the film Blazing Saddles in theaters. It was the top movie of the year, grossing more than $100 million at the North American box office. Blazing Saddles was Brooks’s parody of Westerns, and the targets range from Marlene Dietrich’s Destry Rides Again to farting cowboys and Yiddish-speaking “Indians.” “If we thought of anything,” Brooks recalled in his memoir, “if it even entered our minds, no matter how bizarre or how crazy or dirty or wild or savage or not socially acceptable…we would still do it.”

Brooks also had a higher goal in mind for the movie; Blazing Saddles tackles racism and white supremacy. With co-writer Richard Pryor, one of the most socially provocative stand-up comedians at the time, Brooks made racism the central point of conflict in the film. “Racial prejudice is the engine that really drives the film and helps to make it work,” Brooks wrote. Despite its absurdities, this helped ground the film and give it resonance in an era when segregation was still a recent memory.

Perhaps the scene that best captures the social and political message of Blazing Saddles, at least from a Jewish perspective, is the one in which Sioux Indians speak Yiddish. By comically connecting Jews with American Indians, Brooks nods toward the fact that both Jews and American Indians struggled with persecution in America.

The same year Blazing Saddles was released, 1974, Brooks premiered Young Frankenstein, a parody of classic black-and-white horror films. The movie made $86 million at the box office and, despite being released in December, managed to be the fourth-highest-grossing movie of the year. This gave Brooks two of the top five movies of 1974, an astounding accomplishment akin only to Spielberg at his prime. Frankenstein is largely a parody of old Hollywood monster films, but features a diverse range of Brooks’s trademark jokes: from the assistant, Igor, having an inconsistent hump, to references to Frankenstein’s monster’s large “schwanzstüker.” Gene Wilder, a co-writer of the film, stars as Dr. Frederick Frankenstein who, in a knowing joke about Jewish assimilation, insists his name is pronounced “Fronkensteen.” Beneath the surface, Brooks sought to bring depth to the movie with an “emotional give-and-take.” The message of the movie seems to be that society can create, or make people out to be, monsters. The point is made memorably in a scene where Wilder and Peter Boyle, who plays Frankenstein’s monster, perform a soft-shoe routine to Irving Berlin’s “Puttin’ on the Ritz.” Their performance is not only funny but deeply touching. The lesson to us is the importance of understanding and dwelling with outsiders, core to the historical Jewish experience.

The remainder of Mel Brooks’s career relied on a similar formula of juvenile genre parody coupled with a cast of lovable freaks: Silent Movie; High Anxiety; History of the World, Part I; Spaceballs; and Robin Hood: Men in Tights. Puns, gross-out humor, and lewd jokes abound in these films. The humor was never cruel, and it was always accessible to the lowest comedy denominator: “The only requirement for a Mel Brooks film is that you come in ready to laugh,” Brooks wrote in his memoir. Social commentary was largely absent from these late-career excursions, but History of the World, Part Inotably tackles the “15—oy. 10! Commandments” of Moses and the Spanish Inquisition in a hilarious musical number. In the age of Beverly Hills Cop and Ghostbusters, Brooks’s 1950s comic sensibilities seemed formulaic. Nevertheless, his later movies caught on through VHS and television reruns, creating a new generation of younger Mel Brooks fans.

These movies also displayed another admirable quality of Brooks’s oeuvre. He never forgot his friends. Once you were in a Brooks production, you were included in his extended repertory company, inspired by Brooks’s experience in variety television at the start of his career. Sid Caesar, many years past his prime, was brought back as a studio executive in Silent Movie and as a caveman in History of the World, Part I, precisely the kind of role he loved to perform on Your Show of Shows. Carl Reiner, another Caesar veteran and co-star in Brooks’s “2000-Year Old Man” act, was featured as God in that same movie. Gene Wilder, Harvey Korman, Madeline Kahn, Dom DeLuise, Marty Feldman, and Cloris Leachman all benefited from his famous loyalty, despite the fact that most of them were not big-name stars. Brooks gave his friends all the chances he could.

He also introduced new talents, giving a chance to those who might not have succeeded without his seal of approval. Early on, Gene Wilder earned his big break in The Producers and remained a Brooks mainstay ever since. Other writers found their start on Brooks movies, like Barry Levinson, who co-wrote Silent Movie and High Anxiety and went on to direct 1987’s Rain Man, which grossed more than $350 million and won Levinson Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director. Through his production company, Brooksfilms, Brooks was also able to finance movies that would have otherwise not been greenlit. The most famous of these was 1980’s Elephant Man, which launched director David Lynch’s film career. Brooks even brought in an inexperienced dentist and an equally amateur lawyer to co-write Blazing Saddles. “They were just so wrong, that they were absolutely right,” he recalled. Both writers, Alan Uger and Norman Steinberg, went on to later success writing for television. Late in his career, Brooks cast a young Dave Chappelle for the role of Ahchoo in Men in Tights.

While Mel Brooks has not directed a movie since 1995’s Dracula: Dead and Loving It, his influence in comedy remains immense. Generations of Jewish comic writers and performers have cited him as an influence, including Lorne Michaels, Rob Reiner, Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, Mike Myers, Adam Sandler, Ben Stiller, Sarah Silverman, Judd Apatow, Seth Rogen, and Jonah Hill. And those are just the Jewish comedians! He successfully mixed broad, accessible, and even crude humor with love for the characters and an engine of optimism about individual human beings. And while Brooks clarified that his humor is not “purely Jewish,” he brought Jewish comedic sensibilities to the mainstream. Brooks is a true mensch, and in his own way helped bring Jewish values to the world.

Suggested Reading

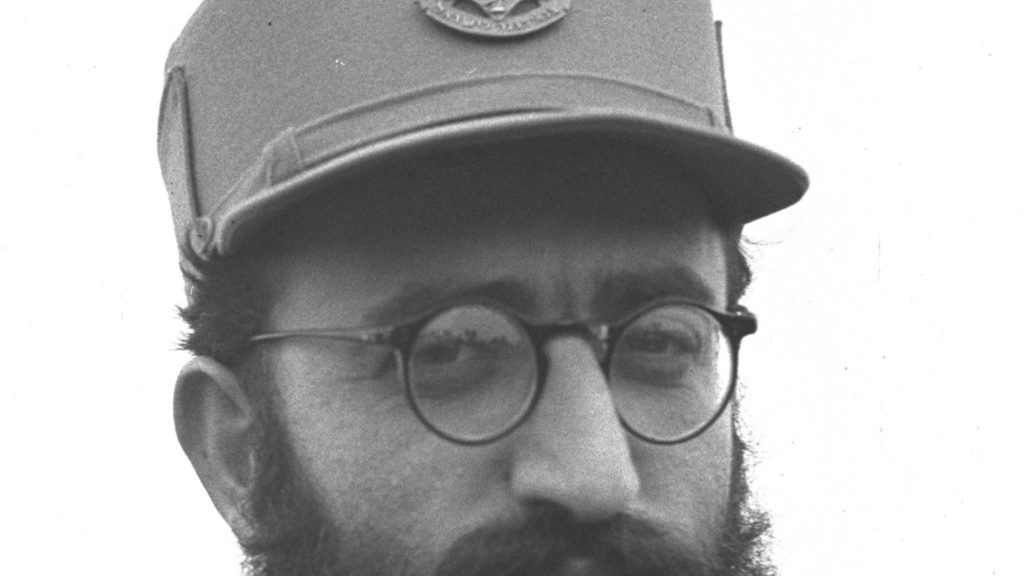

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

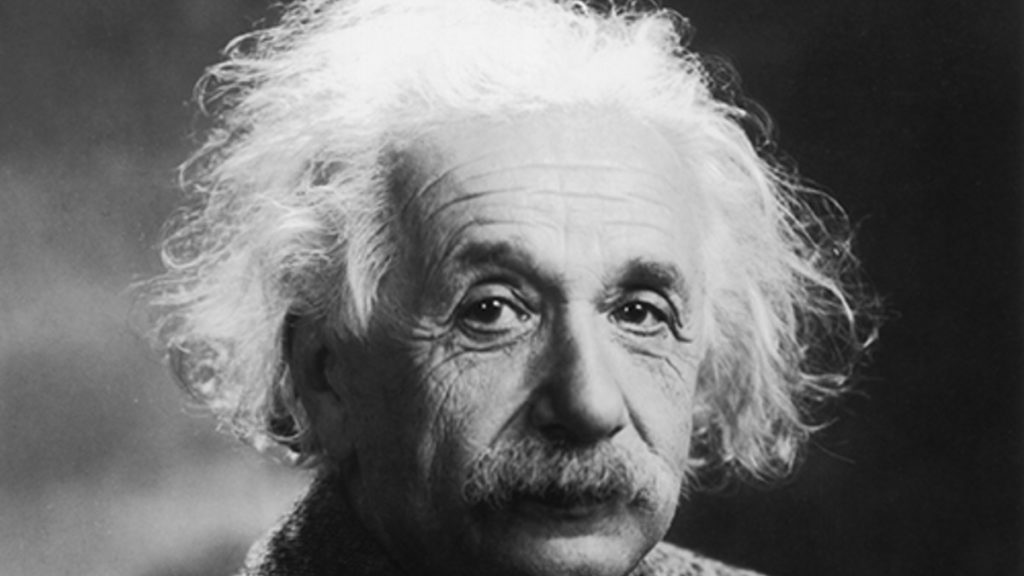

Einstein’s Recalculation of Zionism

Walter Isaacson’s 2007 biography of Albert Einstein—Einstein, His Life and Universe—provides a compelling and detailed account of the scientist’s life as well as insights into his scientific and political views.

Begin’s Jewish Pride

On May 12th, 1977, in the immediate aftermath of his improbable Israeli election victory, Prime Minister-elect Menachem Begin broke down Israel’s long-upheld “secular wall,” as he donned a kippah and…

Rabbi Akiva’s Heroism for Torah

Towards the end of the Second Temple Period, the Land of Israel was in tumult. Following a bloody civil war, the Jews rebelled against the Roman Empire, which had ruled…