Fortifying the “Torah” in Torah u-madda: A Plea to Modern Orthodox Day Schools

BY JOSH STIEFEL

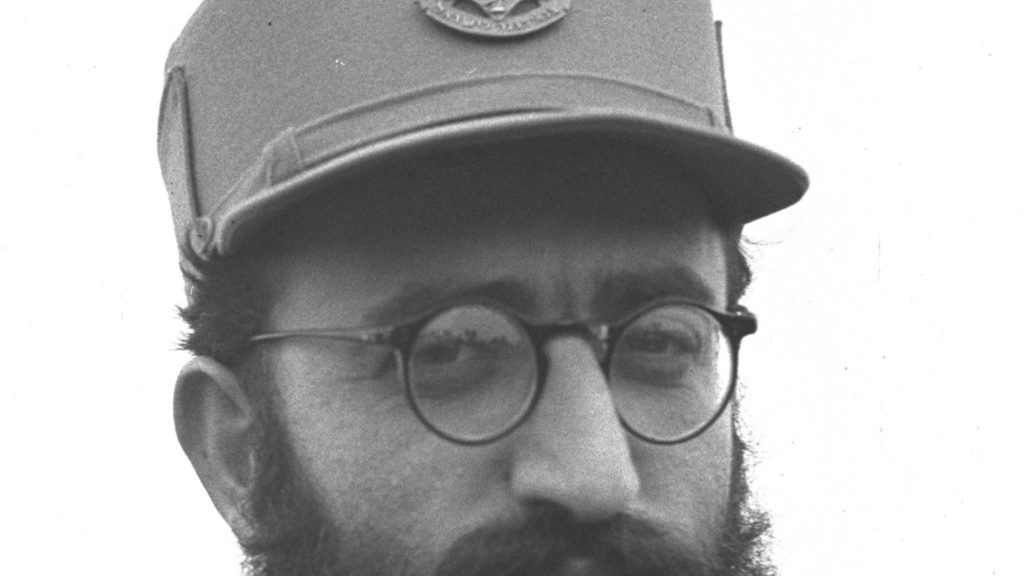

In 1957, the literary scene in Paris was dominated by existentialists and expatriates whose lofty novels formed the backbone of Western literature in the post-war period. These writers, whose profound influence was felt for generations, included such grand figures as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and James Baldwin. And from the confines of the dingy Beat Hotel at 9 Rue Gît-le-Cœur, the 31-year-old Jewish writer Allen Ginsberg added his name to the list when he began the momentous composition of “Kaddish,” an elegiac poem that would shake the foundations of the literary world.

When he began “Kaddish,” Ginsberg had already made a name for himself

as the seminal voice of the Beat Generation, a newly established school of poetry created by Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs in New York City. The Beats, as they became known, were a generation of poets dedicated to the veneration of the tragic figures of America’s grimy underbelly. In Kerouac’s infamous words, the Beats revered “the new angels of the American underground.” Ginsberg spurred the irreverence of the Beats’ iconic identity, as his gritty and emotionally charged writings were often imbued with expletive language and references to homosexuality.

With his explicit verse—eventually the subject of an obscenity lawsuit in the Supreme Court of the United States—Ginsberg revolutionized poetic form. Indeed, under Ginsberg’s guidance, the Beats staged readings of poetry over musical accompaniment—more akin to concerts than poetry readings. As

true masters of these spectacles, the Beats would read their works before crowded venues in sermonic tones, making soaring appeals to the spirits of the American zeitgeist. Amid this melodramatic influence, Ginsberg introduced an almost religious veneration to this new school of poetry. Within the Beats’ writing, a thread of Jewish mysticism, or Kabbalah, runs deep; this influence became instrumental in the composition of “Kaddish.”

Kabbalah first reared its head within Beat literature as a method of emotive expression. With its introduction, Ginsberg opened the floodgates to a world of spiritual poetry, which, in its breadth, enjoyed a popularity that can be best compared to Walt Whitman’s transcendentalism. The Beats were a diverse group of individuals, so it follows that Kabbalah posed different influences for each of the Beat disciples it created. But, regardless of which form Kabbalah assumed, there was a notable consistency in its usage. Even at the hands of Jack Kerouac, a religious Catholic, Jewish mysticism became a tool for literary emotion.

In this respect, the spirit of a particular American Judaism was granted its own space inside the heart of the national Beat culture, a culture originally founded largely in tension with religion, to say nothing of traditional Judaism. Nevertheless, the intermingling of a uniquely Jewish worldview with popular culture became a unique effect of Ginsberg’s work, as Jewish philosophy became enshrined within the mainstream of American literature.

To understand the profound effect of kabbalistic influence on the Beats, understand the cultural nuance of Ginsberg’s childhood religious development in the town of Patterson, New Jersey. Born on June 3, 1926, Ginsberg grew up a secular Jew in the wake of Patterson’s cultural renewal at the hands of the Imagist poet William Carlos Williams, who became Ginsberg’s literary idol. Allen’s father, Louis Ginsberg, was a local school teacher and poet, and his mother, Naomi Levy, was a Russian immigrant and dedicated communist. From a young age, the Ginsberg home was dominated by Naomi’s schizophrenia, which often drove her into sudden and uncontrollable fits of paranoia and psychosis.

The influence of Naomi’s mental illness was profound; even after the young poet left his home for Columbia University, he was still haunted by what he refers to in his poem “Howl” as the “shade of [his] mother.” It was in the wake of this childhood trauma that the maturing poet first encountered Kabbalah. During his time at Columbia, the tension of Ginsberg’s childhood caught up to him, and he suffered what his doctors called a psychotic episode. Ginsberg in his wry mysticism called it a “cosmic vibration breakthrough.”

Yet, despite the concerning health ramifications of this experience, there is no doubt that the poet underwent a religious awakening. When he emerged from the episode, Ginsberg immersed himself in the writings of Gershom Scholem and Martin Buber, from which he derived his own set of kabbalistic beliefs. The two thinkers, themselves giants of twentieth-century Jewish literature, were firm believers in the transcendentalism of Jewish faith. They believed in a Jewish gnosticism, or a spirituality that took precedence over all textual and halakhic thought.

But proponents of gnosticism were an extreme minority, as its acceptance

is tantamount to heresy for many Jews. In Ginsberg’s time, the movement existed as a sectarian offshoot of traditional kabbalistic spirituality, effectively isolated from traditional Orthodox Judaism through their rejection of halakha. The primary basis for this separation lay in the gnostic belief in esoteric biblical codes, which would steer the believer on the path to a spiritual “good”; more traditional Orthodox Jews believe in no such thing. For Ginsberg, this particular idea was epiphanic; as a lover of Walt Whitman, Ginsberg was quite familiar with transcendentalism, so kabbalistic literature appealed to his every sense of poetic identity.

Ginsberg was missing one single piece for the implementation of Kabbalah into his long-standing literary style: integration with Beat culture. This obstacle, however, was easily surmountable, as Ginsberg merely forged a new identity for his poetry under the moniker of “Bop Kabbalah,” a play on

a popular term for 1960s hippie culture. This identity perfectly encapsulated Beat style, in which the everyday figures of American folklore became one with a greater spiritual consciousness. Thus, for Ginsberg, the convergence of Jewish spirituality with American cultural identity was an inevitability.

Jewish faith and mysticism exerted deep influence on Ginsberg and inspired the poet to create a whirlwind mix of the secular and religious. But he did not allow these newly discovered religious teachings to constrain his profanity. For the poet, the mere question of devaluing his artistic production in the name of religious values was absurd. Ginsberg’s ideals followed a specific theme—an exploration of the outer boundaries of human morality in all areas. Gnosticism took root as a conferrer of poetic license, permitting Ginsberg to explore his own esotericism through empirical observations of everyday life. In this respect, Jewish transcendentalism and American grit met within Ginsberg’s poetry as a blend of consciousness, exemplifying the artist’s particular American Jewish experience.

It is from this entanglement of spirituality and irreverence that “Kaddish” was born.

Composed and dedicated as an elegy for Naomi Ginsberg, the poem was written in tragic memoriam following Naomi’s death in 1956. Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, is monotonically recited during daily prayer services for an eleven-month mourning period following the passing of a close family member. As such, the prayer is the ideal framework for a Beat poem, as it thoroughly captures the mysticism of death amid the biting pain of a tragic loss. It is in this style that Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” begins: “Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village.” From the very outset of the poem, Ginsberg delves into the relationship between reflection and death.

Yet the poem’s tone soon ascends into a monotone; this is the return of Jewish mysticism in the form of Ginsberg’s own prayer to his mother’s memory.

The poet cries out in ululations to God, begging that He “Take this, this Psalm, from me, burst from my hand in a day, some of my Time, now given to Nothing—to praise Thee—But Death.” This anguished appeal, however, is soon cast to the poem’s periphery, as Ginsberg returns from his mystic heights to the depths of physical suffering—a classic transition in Beat poetry.

Through this return to reality, the poem quickly flashes through a series of vignettes regarding Naomi’s psychosis, in which she enters a mental hospital, returns home, and then relapses into a frantic paranoia that pursues her until death. The Beat progression of spiritual heights and tragedies concludes with a haunting image of Naomi’s grave, which is surrounded by crows who call to Ginsburg, seeking the truth of “an instant in the universe.” This carefully applied usage of mysticism incomparably captures Ginsberg as an individual. With subtle brushstrokes, the profane and holy were wielded with precision by the father of the Beats in this exemplary work of post-war Jewish American art.

It is difficult to pin Allen Ginsberg under one identity. Constant tinkering with religious faiths gave the poet a uniquely ambiguous relationship with his own Jewish identity. Even in “Kaddish,” the influence of Kabbalah is not absolute; it is compounded with the philosophies of Buddhism, Americana, and the author’s personal philosophy. But, for all of its profound reflection on the life of a deeply spiritual yet complicated man, “Kaddish” serves as a window into the soul of Jewish faith within the culture of a secular American world.

The ensuing conflict between Orthodox asceticism, spiritual Kabbalah, and secular culture thus contorts itself into a dilemma for American Jewry—a dilemma that persists today. Ginsberg’s exaltation of gnosis in “Kaddish” demonstrated his own perception of this distinction, as the values of Kabbalah spread themselves through the tapestry of the American spirit. It, however, remains up to each reader to decide whether the culture Ginsberg spent his career devoted to, even once infused with a certain Jewish mysticism, has served American Jewry well.

.

Mr. Josh Stiefel is a senior at the Frisch School in New Jersey.

Suggested Reading

A New Viewpoint on Diversity

Often, it seems that the people who talk about diversity never visit diverse communities. People seem to think that diversity is based on how one looks. True diversity is not about how someone looks, but how they act.

My Real Internal Conflict is Not One of Clashing Interests

When do my Jewish interests and American interests conflict? After much careful internal deliberation, I have concluded that they do not.

Regaining our Power Through Knowledge: The Solution to Rising Anti-Semitism on Campus

An emotional connection to our Judaism cannot be our only solace. Knowledge is the solution to the problem Jewish students face today.

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…