I.L. Peretz’s Legacy: Challenging Jewish Passivity

BY BENJIE KATZ

If any American has heard of the shtetl, the little market towns where a significant portion of Jews in Eastern Europe lived until the early twentieth century, it is almost certainly thanks to the widespread popularity of Fiddler on the Roof. This story portrays the lives of Jews in Eastern Europe and explores the tensions between tradition and modernity, particularly as anti-Semitic sentiment is spreading. Despite this popularity, Isaac Leib Peretz’s name remains, astonishingly, relatively unknown to a large portion of Americans. Peretz, a foremost figure in the development of modern Jewish culture, dominated Jewish literary life in Warsaw practically from the moment he settled there in 1890 until his death. His influence extended far beyond the Polish capital, reaching and inspiring Jewish communities worldwide. Peretz’s writing predominantly grappled with the realities of mid-nineteenth century Eastern European Jewry, and it serves as a critical lens into the early Zionist movement, which was formed largely in response to the traditional and widespread justifications for Jewish passivity. His satirical critiques of this era are key to understanding the motivations behind the founders of the state of Israel and the responsibility of Jews around the world to uphold Peretz’s ideals of Jewish unity and resistance.

Peretz’s “The Shabbos Goy” tells the story of Yankele, a man who lives in the shtetl of Chelm and is consistently attacked by the “Shabbos Goy,” whose job it is to perform certain types of work (melakha) that Jewish religious law (halakha) prohibits a Jew from doing on the Sabbath. Every time Yankele goes to his rabbi to complain about the Shabbos Goy’s constant harassment, the rabbi places blame on Yankele instead. For example, when he is punched in the teeth by the abuser, the rabbi blames him for walking about the shtetl with such beautiful teeth. Eventually, Yankele gets kicked out of the shtetl for endangering the community. As the story concludes, Peretz writes, “You’re laughing? Still, there’s a little of the Rabbi of Chelm in each of us.” The priority of the Rabbi of Chelm was not to protect the dignity of the Jew, but rather to please the neighbors and discourage them from attacking the rest of the shtetl.

Peretz conveys a haunting message to the reader, as he asserts that this is no mere fable; rather, it serves as a stark display of the prevalent tendency within the Jewish community to justify and thus perpetuate the cruelty of the Jews’ oppressors. This form of Jewish passivity was unfortunately pervasive in the diasporic Jewish communities at the time. When pogroms were incited, the citizens of the shtetls toiled to quickly clean up the mess, giving the appearance of normalcy as if the violent events had never occurred. Peretz staunchly disagreed with this response and called for a change in communal mindset, urging Jews to prioritize compassion and care for one another in accordance with Jewish ideals.

Further critique of Jewish passivity can be found in Peretz’s most famous story, “Bontche Shveig,” or Bontche the Silent. Peretz juxtaposes protagonist Bontche’s life of extreme hardship and neglect, which includes pogroms, exile, poverty, and the legal restrictions imposed on Jews, with his unrelenting stoicism and quiet acceptance of this fate. The story begins with Bontche’s death, his unmarked grave symbolizing the lack of recognition he received in life. Yet in the afterlife, the heavenly court is ready to grant him entry without much debate, highlighting the exceptional nature of Bontche’s passive life. The shift in the narrative occurs when Bontche is given the opportunity to request anything in heaven, and his modest wish is for a hot roll with fresh butter every day.

While this could be interpreted as a tale of incredible fortitude, Peretz offers a more bitter commentary, suggesting Bontche is symbolic of the indifference and acceptance of the unacceptable so prevalent in the shtetls. The Jewish persecution of the time makes it challenging to view Bontche’s passivity as a virtue, and Peretz questions Bontche’s attitude. Bontche’s individual story was intended to represent the collective response of Jews in the diaspora to the injustices they encountered, emphasizing the need for an assertive and active stance towards adversity. The debate surrounding Jewish indifference became particularly relevant in the aftermath of the Holocaust, and many turned to the author who had grappled with the idea that Jews were not armed or prepared for the brutality they encountered.

The works of Isaac Leib Peretz offer a profound perspective on the complex dynamics of Jewish passivity, as he skillfully employs satire and storytelling to shed light on the repercussions of silent endurance and inaction. Peretz’s call to action was ultimately answered in the Zionist movement and the establishment of the Jewish state. Jews now have our own country and we are able to assert ourselves militarily in the face of unprecedented slaughter. Peretz’s stories continue to serve as a poignant reminder of the power of the Jewish people when unified and self-confident, as well as the dire consequences of our division.

Suggested Reading

A New Viewpoint on Diversity

Often, it seems that the people who talk about diversity never visit diverse communities. People seem to think that diversity is based on how one looks. True diversity is not about how someone looks, but how they act.

My Real Internal Conflict is Not One of Clashing Interests

When do my Jewish interests and American interests conflict? After much careful internal deliberation, I have concluded that they do not.

Regaining our Power Through Knowledge: The Solution to Rising Anti-Semitism on Campus

An emotional connection to our Judaism cannot be our only solace. Knowledge is the solution to the problem Jewish students face today.

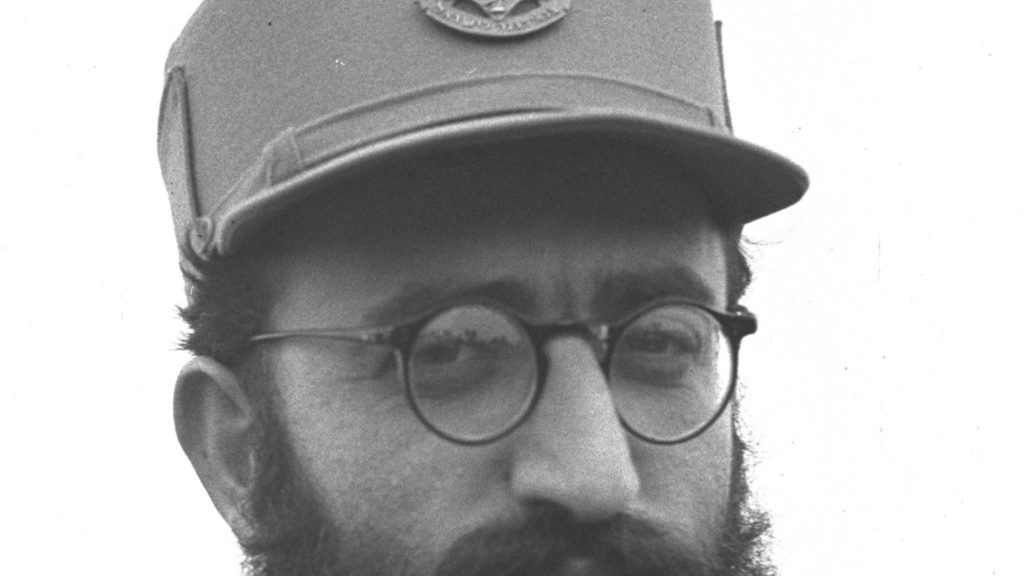

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…