Living A Double Life

BY GALIT ALSAYGH

The Tanakh has a stance on Jews in golah, exile. To assimilate or to isolate? To practice or to neglect? To be active or to be passive? Although these questions may seem particularly piercing for Jews today, the stories of Esther and Daniel make it clear that these have been pertinent issues throughout Jewish history.

In Megillat Esther, the book of Esther, Esther, the heroine, is an orphan raised by her cousin, Mordechai. Mordechai is most often referred to as “Mordechai HaYehudi,” Mordechai the Jew, emphasizing his commitment to God and Judaism. In a miraculous fashion, Esther is chosen to be Queen to King Ahasuerus of the Persian Empire in the same moments that an anti-Semitic zealot and Mordechai’s personal adversary, Haman, is promoted to be second in command. Haman, with the approval of the King, plots to murder all the Jews of the massive 127-province empire, and is naive to the fact that the Queen herself is a Jew. The story ends happily with Mordechai and Esther’s shrewd work to invalidate Haman’s decree, and thus save the Jewish population.

Although the happily ever after comes seemingly overnight, saving the Jews was a process—one that posed the same questions we Jews are faced with today. Do we assimilate into alien culture, or isolate entirely? Should we be active in religious society and culture, or be passive participants? Megillat Esther and its characters offer a simple yet complex answer: both. Assimilate and isolate. Be active and passive.

In the Tanakh, as well as Judaism at large, names often hold deep meanings that reflect a person’s traits, destiny, or role in the narrative, offering clues to the themes and messages of the story. In her commentary on Megillat Esther, Adele Berlin, an American biblical scholar and Hebraist, suggests that Mordechai and Esther’s names, specifically their origins, serve a deeper purpose than meets the eye. Esther’s Hebrew name is Hadassah which means “myrtle,” one of the four species used during Sukkot. Her “secular” name however, Esther, can either stem from Persian or Babylonian roots. She is either named after the Babylonian Goddess Ishtar, or after the Persian word “stara,” meaning star.

Interestingly, unlike Esther, Mordechai does not have a secular name. Berlin argues, however, that the name Mordechai originates from both Babylonian and Jewish culture. For the Babylonians, Mordechai shares the roots of the names Marduka or Marduk, the chief god in Babylon. For the Jews of Babylon, it was merely a common name, with some even naming their children versions of Marduk, with no intention of making a direct connection to the deity. Mordechai and Esther’s dual names are a testament to their dual life; they strike the balance between their religious and secular lives.

Mordechai is a Jewish leader. This is apparent in his defiant actions, including his refusal to bow down to Haman and his insistence on maintaining Jewish tradition. Tradition also tells us that he comes from a long line of Jewish leaders. But Mordechai was also a secular leader. This was apparent in his promotion to second in command at the end of the megillah. So too with Esther, being the Queen of an am zar, a foreign nation, while also being the heroine of the Jewish people. Through their names and actions, the megillah emphasizes that they were Persian Jews, not Jewish Persians.

Similarly, the chronicles of Daniel and his peers, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah, contemplate the same questions. The book of Daniel is a record of events, experiences, and prophecies of Daniel that take place during the Babylonian exile under the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II, in 586 BCE. Daniel’s story begins with the capture of Jerusalem, and the exile of many Jews living there. Among them are Daniel and his peers, who are then chosen to serve on the Babylonian court. Nebuchadnezzar ordered their names be changed before they began their “duty,” yet this was not the case with any of the other prisoners. Daniel became Belshazzar, Hananiah became Shadrach, Mishael became Meshach, and Azariah became Abednego.

By doing so, Nebuchadnezzar asserted his power over the Jewish exiles and highlighted his plan to reshape their identity. The Tanakh then recounts several of their manifestations of loyalty to Hashem, including their refusal to serve the Babylonian gods, even at the risk of being thrown into a fiery furnace. Daniel also refused to eat and drink at Nebuchadnezzar’s feast in order not to defile himself, and was adamant about praying three times a day, again under the risk of death.

Daniel and his friends epitomize how Jews in exile navigated the balance between survival and faithfulness. While they were committed to preserving their Jewish practices and traditions, their actions go beyond pure resistance. Rather than refusing outright to serve in the Babylonian court—a form of resistance that could have jeopardized their lives—they found ways to engage with their surroundings while holding firm to their faith. Their service in the Babylonian court reflects their complex approach to living in golah: they valued their Judaism, but also their life, and thus adapted to their circumstances. They found their “way” to live, whatever “way” it may be.

This raises an important question: is this the balance that Hashem envisions for the Jews of exile? Does this apply, not just to Daniel’s scenario, but to all the stories of Tanakh that take place in golah? And by extension, does this apply to the golah of today?

The commentators of Megillat Esther take opposing stances, some teaching that a balance of resistance and compliance is the only way Jews will thrive in exile. History happens to agree. Whether it was the “Golden Age” of Spanish Jewry in the tenth century, or the Haskalah movement (more commonly known as the Jewish Enlightenment) of the eighteenth century, there were always sects of Judaism that embraced secular culture and education while also embracing religious and Jewish culture and education.

Today, many Jewish communities value Torah u-Madda, the study of Torah and science, religious and temporal subjects. It is in these times that Jewry all over the world flourishes, both in and out of Israel. As former Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis famously said, “To be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.” His words remain a crucial reminder that the key to Jewish flourishing lies in embracing both our heritage and the world around us.

Suggested Reading

“If Only My People…” Zionism in My Life

BY GIDEON ROSEN “And I will give you as a light for the nations so My salvation will reach the edge of the earth” (Isaiah 49:6) In his book, “If…

Begin’s Jewish Pride

On May 12th, 1977, in the immediate aftermath of his improbable Israeli election victory, Prime Minister-elect Menachem Begin broke down Israel’s long-upheld “secular wall,” as he donned a kippah and…

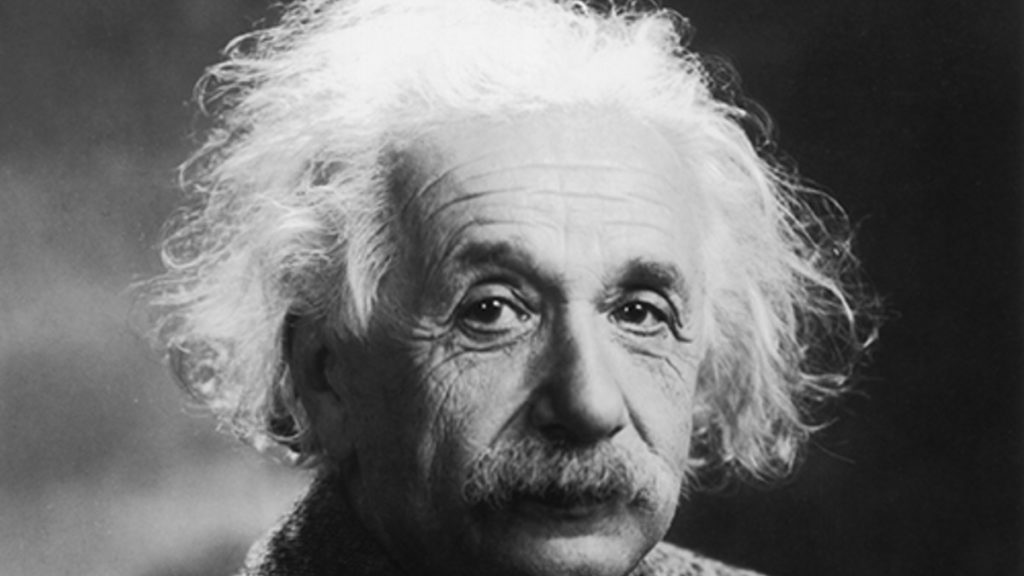

Einstein’s Recalculation of Zionism

Walter Isaacson’s 2007 biography of Albert Einstein—Einstein, His Life and Universe—provides a compelling and detailed account of the scientist’s life as well as insights into his scientific and political views.

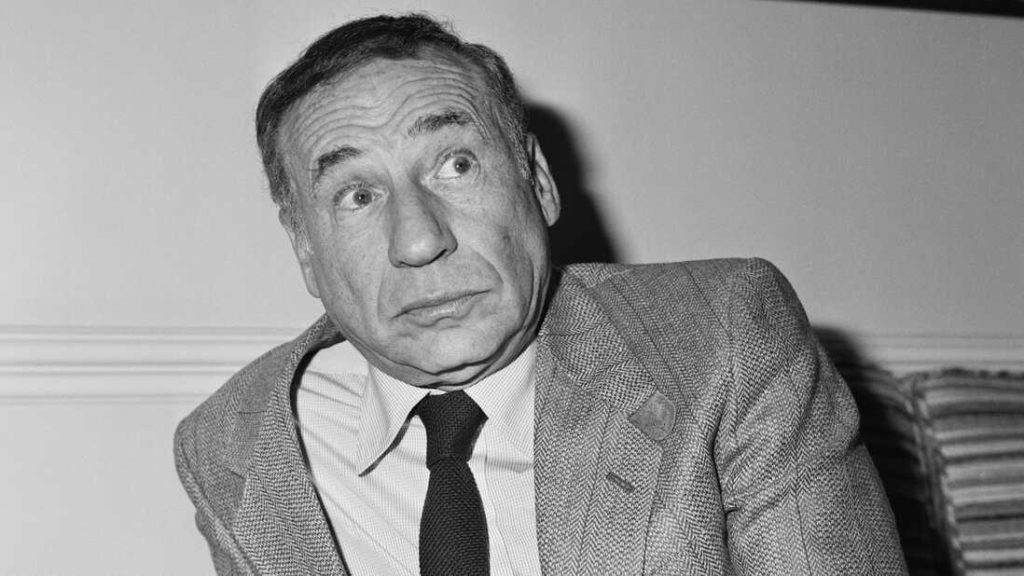

All About Mel

In an iconic moment of the 1967 film The Producers, scantily clad dancers dressed as Nazi sturmtruppen move into swastika formation and slowly rotate, surrounded by Third Reich banners and singers extolling the…