When Rebellion Becomes a Trend: Fashion and the Commodification of Otherness

BY RACHAEL KOPYLOV

Goth fashion, heavily influenced by Victorian and Edwardian elements, was born from the British Punk Movement of the late 70s and early 80s. Although it began as a relatively fringe movement, music journalists attending underground gothic music scenes helped spread the style across Britian and beyond, transforming it into an international phenomenon. Often characterized by black clothing, leather and lace fabrics, platform boots, and edgy accessories, the goth movement served as a safe haven for many who felt ostracized by more mainstream culture—a place for them to embrace what society had rejected. However, despite its roots in rebellion and outsider identity, the goth movement has since become heavily commodified, raising questions about how authentic expressions of “the other” survive when transformed into marketable trends.

Fashion has always been more than the clothes one drapes on one’s body; it is a medium of self-expression and individuality. For many, their personal taste in clothing becomes a way of expressing their “otherness,” forming a counter-cultural identity. The desire to use fashion as protection against societal norms does not only apply to the goth movement.

In the 1960s and 1970s, other countercultural movements surged among Western youth in response to the perceived rigidity of their upbringings, the upheaval of the Vietnam war, and a growing rejection of consumerism. Young people felt increasingly disconnected from their parents’ lifestyles, which they believed put too much emphasis on social conformity and material possessions. Labeled “hippies,” members of this countercultural movement typically wore long hair, colorful shoes and jewelry, and most famously, donned clothing accentuated with flowers—a favored symbol for peace. Beyond their clothing, the hippie attitude extended to their overall lifestyles, which often included communal living, participation in political protests, nomadic living and recreational drug use. By adhering to this counterculture, young people in the West were essentially rejecting the lives of their parents while marking themselves as “others” within their own society.

Similarly, the Harajuku movement, originating from the Harajuku district of Japan in the early 1980s and consisting of various Japanese streetwear styles, also served as a rejection of Japanese society at the time. Japan in the 1980s saw a period of significant economic growth, which led to an extremely homogenous and work-centric society. As a result, unique Harajuku streetwear styles and substyles emerged among the Japanese youth, embodying rebellion and self-expression. The Japanese “Gothic Lolita,” for example, is a style that draws inspiration from Victorian and Rococo fashion, featuring frilly dresses, elaborate accessories, and an almost doll-like aesthetic. Another style, “Visual Kei,” was influenced by Japanese rock music and is characterized by flamboyant costumes and dramatic makeup, projecting the theatricality of the music genre. Both substyles starkly contrast with the elegance and structured silhouettes popular in mainstream Japanese society. Nonetheless, just like goth fashion, these expressions of “otherness” were discovered, commodified, and eventually assimilated into the mainstream tastes and societies they opposed.

The pattern described above, where countercultural movements are eventually assimilated into the mainstream culture, reflects a deeper paradox about culture and self-expression in modern society. The German-American philosopher and political theorist Herbert Marcuse offers us a lens through which to understand this process. In his 1964 book, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society, Marcuse examines the concept of “repressive desublimation,” the idea that methods of “rebellion” are used as tools of repression, stripping these movements of their radical edge.

Marcuse’s argument borrows from Sigmund Freud’s idea of “sublimation,” the process by which individuals reroute destructive, instinctual drives into socially valued forms like art and science. In Freud’s view, “sublimation” is not only a way to civilize society, but to also advance culture. By contrast, Marcuse’s “desublimation” occurs when these instinctual drives are expressed directly rather than being channeled into higher forms. For example, instead of releasing feelings of alienation by creating experimental fashion or music, individuals might seek immediate gratification through purchasing mass-produced “rebellious” products or partaking in trends that mimic “otherness” without actually committing to their original meaning. According to Marcuse, desublimation is a repressive practice. Repression, in his philosophy, is perpetuated not through controlling and denying these desires, but through supporting and even fostering them—only in a commodified form. This creates an illusion of freedom because it allows people to think that they can express themselves however they please, but in reality, their “self-expression” is being funneled into predictable, marketable forms.

The paths of goth, Harajuku, and the hippy counterculture clearly illustrate Marcuse’s idea of “repressive desublimation”: each began as an oppositional movement, only to be subsequently aestheticized and commercialized. Black lace dresses and chokers, once symbolic of unique identity in goth culture, now hang in popular fast-fashion retail stores like Hot Topic; hippie bell-bottom jeans and tie-dye shirts are now marketed as “boho-chic” and “festival-wear”; Harajuku’s formerly radical aesthetic has become globalized and stripped of its original context. When styles founded on ideas of “otherness” are absorbed into the mainstream, they lose their ability to incite outrage and instead reinforce the systems they were built to oppose. Fashion can serve both as a method for liberation and as a mechanism for control, offering some the illusion of freedom while simultaneously reinforcing conformity.

Although Marcuse provides a powerful critique of the commercialization of rebellion, he’s not without his critics. The French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault questions whether Marcuse’s theory leaves enough room for nuance. In his most famous work, The History of Sexuality, Foucault criticizes Marcuse’s “repression hypothesis” for being overly pessimistic. While Marcuse believes that power subdues rebellion, Foucault takes the opposite approach, arguing that power is actually productive, shaping and creating new desires and social movements. When discussing fashion movements and subcultures, Foucault argues that when these movements become commercialized, the intentions behind them don’t get removed, but actually continue to evolve. While gothic fashion, hippie counterculture, and Harajuku may be more mainstream and accessible today, they still offer a community where individuals have the opportunity to challenge cultural norms. According to Foucault, subcultures are not passive victims of the market, despite them existing within, or even being shaped by, the wider structures of power and commerce.

The evolution of countercultural fashion movements reveals a paradoxical relationship between rebellion, identity, commerce, and power in modern society. While many of these styles originally emerged as an expression of “otherness,” they continue to enter the mainstream through commodification and mass-production. Some thinkers, like Herbert Marcuse, view this cycle pessimistically; each movement eventually rendered meaningless. However, as Michel Foucault points out, subcultures are not completely nullified when they appear in the mainstream; they still have the ability to grow their communities while retaining their original purposes. Ultimately, fashion is a dynamic industry where the desire for individuality is forced to coexist with commercialization. Despite this challenge, the resilience of subcultures like goth, hippie, and Harajuku demonstrate that “otherness” can persist even within commodified spaces.

Suggested Reading

Shining Our Light Unto the Nations Through Jewish Teachings

BY ADIN LINDEN Jewish history is rife with enemies, from the Egyptians to the descendants of Amalek, a lineage that is seen as the greatest enemy of the Jews and…

Between Separating Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in Others

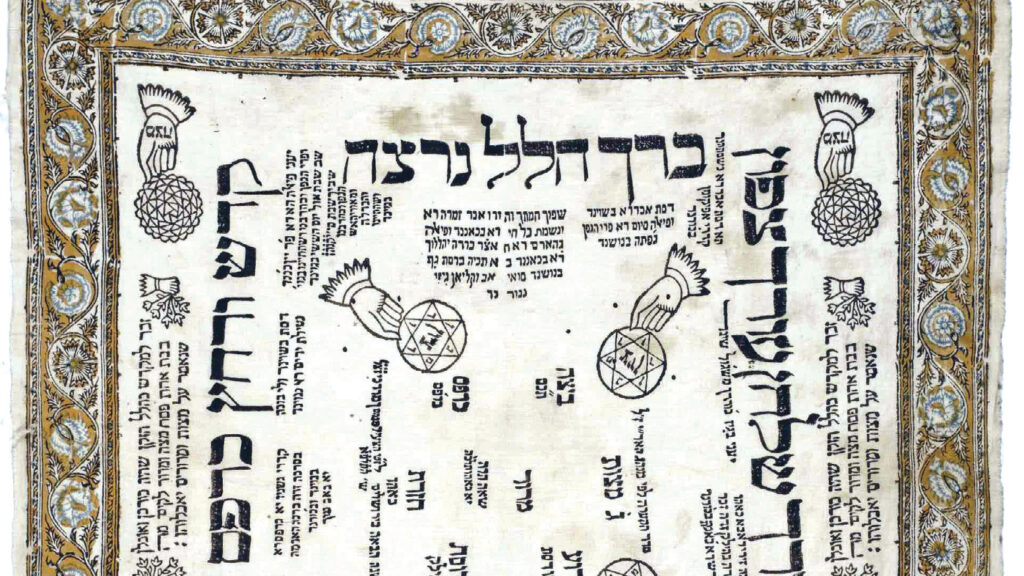

BY YAEL BURGESS EISENBERG When a gentile came before Hillel and said he would convert to Judaism if Hillel could teach him the entire Torah while standing on one foot,…

Fortifying the “Torah” in Torah u-madda: A Plea to Modern Orthodox Day Schools

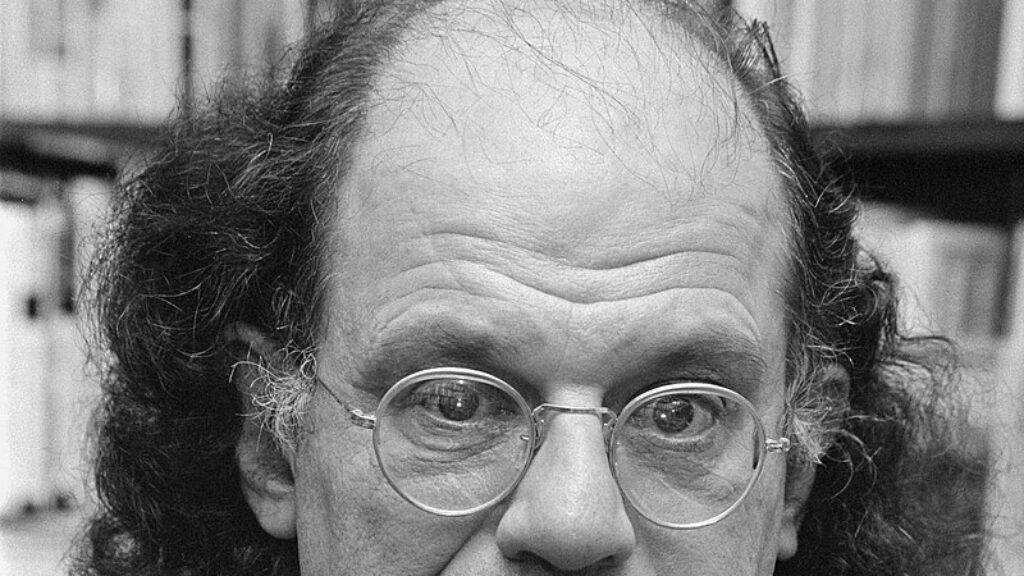

In a deep look at his background and motivations, the picture of Jewish writer Allen Ginsberg becomes more clear to the observer. His difficult past and masterful mix of secular, religious, and kabbalistic, as well as various other, themes in his work came to a head in his poem "Kaddish", written to be an elegy for his mother.

Learning as Creation: The Power of Jewish Education

BY ZACHARY KROHN It is no secret that education is one of the highest values of Judaism, and one can give many reasons for why that is the case. Education…