Proud Jews in Public Schools

BY CHANI SINGER

Reading an article by Moriah Schranz, titled “The Out-of-Town Jew,” in the last edition of the Solomon Journal, inspired me to tell a similar story about how, as an American Jew who attends public school, my relationship to Judaism shifted after October 7, 2023.

I have attended public school since I was in seventh grade. As an Orthodox Jew, my religion and connection to Israel have always been a core part of my identity, but they were not things I necessarily advertised about myself. Though I attend a very diverse magnet school in Dallas, I am one of only seven Jewish students at my school, and the only Orthodox Jewish student. After October 7, I felt completely suffocated by the constant discussions about the Middle East that were taking place at my school.

These public conversations, consisting mainly of criticism toward Israel, made me realize how foreign Judaism—as a religion, culture, and history—is to most people. All around me, people were making baseless claims about Israel’s motives and its response to the October 7 attack. I felt extremely isolated and unsure of how to carry myself as a Jew in such a hostile environment. It felt like I was stuck with only two options: fight or flight.

At first, I chose flight. Like many others, I was surrounded by people at school who would make anti-Israel comments, wear pro-Palestinian merchandise, or post content on social media in support of Palestine. Though I am fortunate to have had limited direct exposure to anti-Semitism related to the war, I still encountered it a couple of times. About a month after the war broke out, in early November 2023, I noticed several posters hanging in the hallway of my school about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In a mandatory ninth grade class at my school, AP Human Geography, there is a unit in which students learn about various global conflicts, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As a final project, students are assigned a conflict to research, create posters about, and display in the hallway for others to read.

I knew these posters were full of misinformation, but I had not examined them closely until I saw that students were stopping to read them. That is when I realized people were really using these posters to learn about world events. Horrified, I got up to see what others had been absorbing as truth. None of the posters mentioned the October 7 attack on Israel or any historical context about Gaza. On the timeline of one of the posters, in the segment labeled “2005–Present,” the only event listed was Israel’s “blockade” on Gaza and its impact on the Gazan economy. The information was completely skewed, if not outright inaccurate.

Another poster’s timeline jumped from the “Six-Day War in 1967” to “Now,” claiming that all Palestinians had been “closed into the Gaza Strip and West Bank” and that Israel was “bomb[ing] them constantly,” with no mention of Israel’s experience with terrorism and need for defense. Additionally, on the map displaying the territory, Gaza is drawn in the wrong location, only bordering Egypt and Israel, and without its coastline along the Mediterranean Sea. These posters overflowed with misinformation, and the narratives students were absorbing were completely erroneous. Though this was very troubling, I did not yet feel singled out.

Then, in February 2024, it became personal. It was the Monday after the Super Bowl and the hostage rescue in Rafah. Unprompted, my English teacher started talking about Israel, claiming that the Israeli government used the Super Bowl as a “distraction in the media to make moves on Gaza.” In front of my entire AP English class, he went on a thirty-minute rant, saying that, though the Israeli government claims they are trying to take out Hamas because it is a terrorist organization, it’s really just because “they are brown.”

My classmates listened intently as he continued making claim after claim about Jews in America, Jews in Israel, and the war. Some of my friends glanced at me, wondering if I was going to respond. I chose not to, realizing that my teacher was not trying to engage in a conversation, but wanted to express his own opinions and theories as facts. At that moment, I felt threatened and insecure as a Jew.

These two encounters with anti-Israel bias and anti-Semitism at school helped me recognize a common pattern many people follow when learning about a new topic. There are four clear stages of knowledge, confidence, and understanding that I would like to address.

At first, a person knows absolutely nothing about a topic, and therefore does not feel comfortable discussing it. Then, we learn a little—just enough to scratch the surface. Maybe through browsing some Instagram pages, watching a few videos on TikTok, or reading a couple of articles. People in this stage often feel that, because they have spent some time learning, they know enough to confidently express their stance. Ironically, they are often the loudest.

The third stage is when a person learns some more and realizes the topic is far more complex than they initially thought. At this stage, people often feel hesitant to discuss the subject, recognizing their limited understanding. Finally, the last stage is when a person has dedicated significant time to educating themselves and others, allowing the person to accurately explain the topic and his or her views on it with nuance. Many people remain stuck in the second stage, including the ninth grade students who made the posters, many of my peers reading the posters, and my English teacher.

These experiences helped me realize that although there are only a few Jewish students at my school, we need to have a voice. We deserve the opportunity to educate people about Judaism, our culture, and our shared connection to Israel. So in September 2024, my Jewish peers and I started a Jewish Student Union. Every month, the board, composed of the seven Jewish students, works together to organize an event centered around an upcoming Jewish holiday or Jewish tradition. These events are open to anyone who wants to attend, and we typically have around 30 students participate. We have successfully created a space where people feel welcome to learn, ask questions, and explore the beauty of our culture in a space created by proud Jews.

As people learned more about Judaism, they began asking me more questions about Jewish practices. I received questions from classmates about kashrut, Shabbat, halakha (Jewish law), and the Jewish connection to Israel. Some did not know that Judaism is not just a religion, or what makes someone Jewish according to halakha. Most students didn’t realize that Jews come from all different backgrounds. Almost no one knew that Jews make up only 0.2 percent of the world’s population.

Some of these questions I could answer immediately, while others required further research. Regardless, every question strengthened my pride as a Jew. When I am prompted to learn more about my practices, I find deeper meaning in them. When I get to share my culture with others, I feel more fulfilled. As a religious Jew in a secular environment, I have not only strengthened my outward identity but also deepened my personal practice.

My Jewish pride has become my armor. Though I was initially hesitant to open up about my Judaism, doing so ultimately made my connection to it stronger.

Suggested Reading

Shining Our Light Unto the Nations Through Jewish Teachings

BY ADIN LINDEN Jewish history is rife with enemies, from the Egyptians to the descendants of Amalek, a lineage that is seen as the greatest enemy of the Jews and…

Between Separating Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in Others

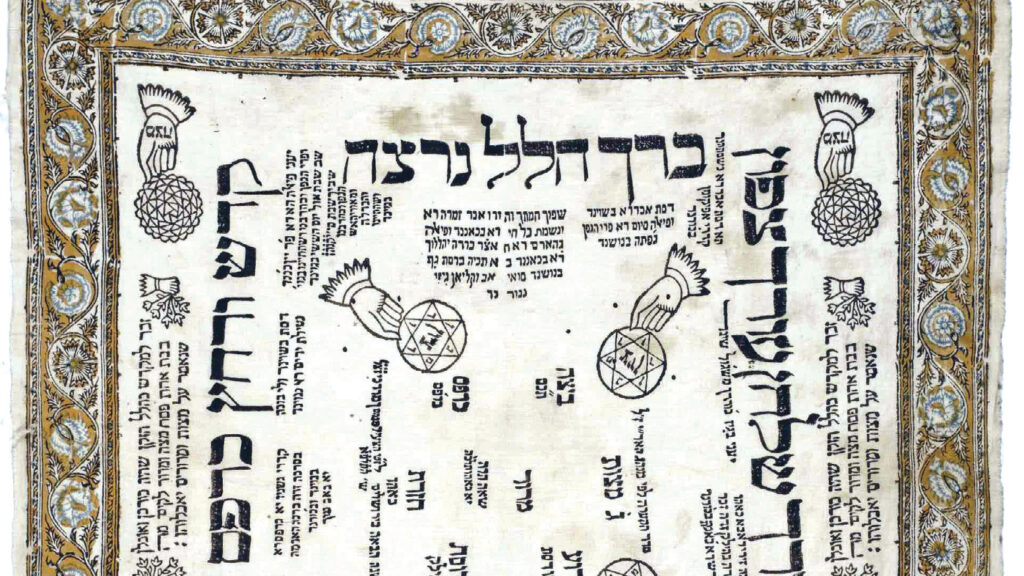

BY YAEL BURGESS EISENBERG When a gentile came before Hillel and said he would convert to Judaism if Hillel could teach him the entire Torah while standing on one foot,…

Fortifying the “Torah” in Torah u-madda: A Plea to Modern Orthodox Day Schools

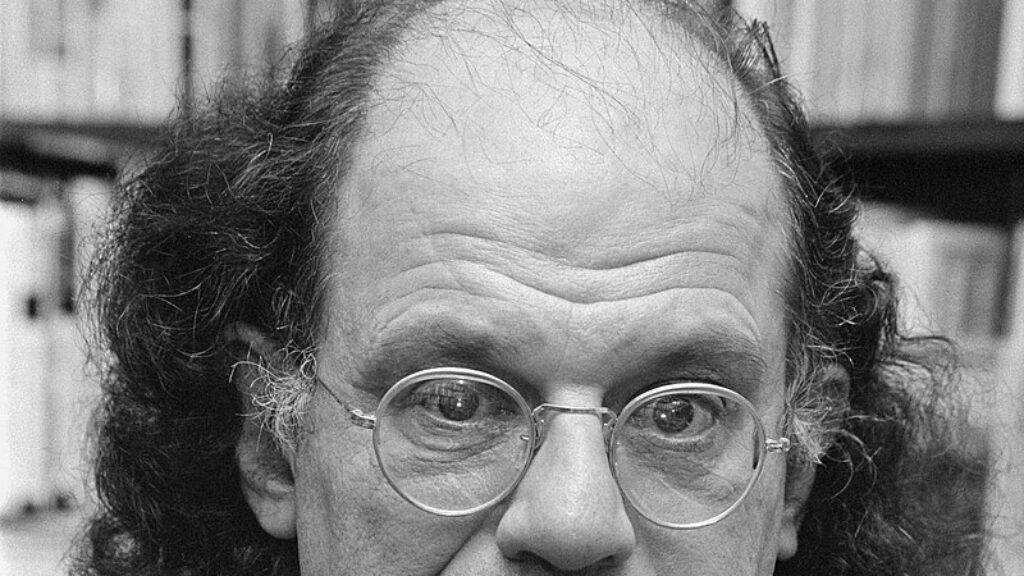

In a deep look at his background and motivations, the picture of Jewish writer Allen Ginsberg becomes more clear to the observer. His difficult past and masterful mix of secular, religious, and kabbalistic, as well as various other, themes in his work came to a head in his poem "Kaddish", written to be an elegy for his mother.

Learning as Creation: The Power of Jewish Education

BY ZACHARY KROHN It is no secret that education is one of the highest values of Judaism, and one can give many reasons for why that is the case. Education…