Babel and Job: Where Human Certainty Meets Divine Truth

BY BENNY MARMOR

The narrative of the Tower of Babel only lasts nine verses and is sandwiched between two genealogies of the sons of Noah, yet it is one of the most famous and well-known stories in the Book of Genesis. Seemingly an afterthought to the story of creation and the flood, it is a story about humanity, united by a common language, deciding to build a tower to the sky in the land of Shinar—soon to be renamed Babylonia.

Why do the people embark on such a project? “Lest we be scattered abroad on the face of the whole earth,” they declare. God disapproves, and descends to stop their work; as punishment, God disperses humanity and “babbles” their speech, providing us with the origin for Babylonia’s name. The simplicity of the story is deceptive, and, despite its brevity, the story has inspired pages of commentary attempting to answer the question at the heart of the narrative: where exactly did humanity go wrong?

As stated above, this puzzling story only spans nine verses; of those nine verses, God only speaks in one of them. As such, this verse is central to understanding the mystery at the heart of the story.

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ה’ הֵ֣ן עַ֤ם אֶחָד֙ וְשָׂפָ֤ה אַחַת֙ לְכֻלָּ֔ם וְזֶ֖ה הַחִלָּ֣ם לַעֲשׂ֑וֹת וְעַתָּה֙ לֹֽא־יִבָּצֵ֣ר מֵהֶ֔ם כֹּ֛ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר יָזְמ֖וּ לַֽעֲשֽׂוֹת׃

“And the LORD said: ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is what they begin to do; and now nothing will be withholden from them, which they purpose to do” (Genesis 11:6)

God articulates three fundamental problems with humankind’s behavior. First, that they are one people with one language; second, the inherent act of building the tower is problematic; and third, that “nothing will be withholden” from humankind, nothing holding them back from that which they wish to do.

The Netziv, a nineteenth-century Torah commentator, highlights these elements of God’s response and provides a powerful account of this Dor Hapalagah (Generation of the Dispersion). Drawing from Midrash, previous commentators, and his own unique approach to biblical text, the Netziv weaves together disparate interpretations to claim that the sin of the tower’s builders was that of uniformity.

To the Netziv, “one people” and “one language” describe a totalitarian society intolerant of dissent, building a tower so dominating as to ensure that nobody wanders away to create an alternative community. The Netziv imagines a literal watchtower, enabling the tower’s builders to spot nonconformists attempting to leave the land of Shinar. He describes how those caught with different views would actually be burned. The Netziv seemingly pulls this interpretation from other Midrashim that identify the leader of the builders as Nimrod, who is described in later midrashic stories as throwing the patriarch Abraham into a furnace when Abraham publicly challenged Babylonian polytheism and recognized one God.

With the Netziv’s commentary on the motivations and dynamics of the people depicted in the Genesis narrative, we can attempt to better understand the last part of God’s cryptic declaration. The Jewish Publication Society (JPS) Tanakh renders the phrase as “nothing will be withholden from them, which they purpose to do.” However, this translation is ambiguous; is God alluding to the power of a common language or the strength of their new city? Additionally, the translation of the verb “יבצר” as “will be withholden” adds to the confusion. Why is the text phrased in this way?

The Hebrew root word “בצר” usually appears in the context of a fortress, but also to refer to famine; when used as a verb, it often appears in the context of cutting grapes or diminishing. As a verb, it appears with similar vowels in the Book of Jeremiah (51:53) with the meaning “to fortify.” By reinterpreting the verb “יבצר” as “they will fortify,” instead of “will be withholden,” a clearer translation of the text emerges, one that reinforces the Netziv’s idea:

“And now, those who do not ascribe to the tower builders’ ideology will not fortify themselves against the builders of the tower, no matter what the builders of the tower initiate to do.”

If, according to the Netziv’s translation, the dissenters are silenced, the continual exchange of ideas will cease. There will be no need for the “fortification” of one’s ideas. Dissenting opinions that run counter to those of the ruling power become futile. No one will disagree, because with one language and a completed tower, no one can leave. A biblical totalitarian rule emerges, which necessitates divine intervention.

Like the story of the Tower of Babel, the Book of Job deals with similar themes; both narratives explore the limits of human ingenuity when compared with an infinitely powerful God. The Book of Job describes the attempts at theodicy by Job and his friends as they try to make sense of the suffering inflicted on Job. God rebukes Job and his three friends, reminding them that He is outside the realm of human understanding. After God’s rebuke, Job employs the same language as found in the Tower of Babel story, providing something of an apology while describing his own inadequacy and inability to fully comprehend God’s vision for the world.

(ידעת) [יָ֭דַעְתִּי] כִּי־כֹ֣ל תּוּכָ֑ל וְלֹֽא־יִבָּצֵ֖ר מִמְּךָ֣ מְזִמָּֽה׃

“I know that Thou canst do everything, And that no purpose can be withholden from Thee” (Job 42:2)

Pay attention to the striking parallels between this verse and the language from Genesis. Job 42:2 is the only other place in Tanakh where the roots בצר (withhold/fortify) and זמם (initiate) appear together. However, instead of the language being used by God to describe man (as in Genesis), here man is attempting to describe God. The Hebrew sentence structure and vowels on יבצר are identical in Genesis and in Job. Reinterpreting the Job verse to refer to fortification yields this result: “I know that you can do anything, and no one can fortify [themselves] from what you initiate.”

Together, the stories of the Tower of Babel and the suffering of Job shed light on each other and speak to a parallel truth of human existence. The Dor Hapalagah in Genesis teaches us the importance of allowing difference to make its voice heard. No individual should impose their singular experience of the world on others. The Book of Job cautions us that humans are wise but fallible, and despite the importance of human agency, there is still God’s ultimate truth that must be heeded.

Ultimately, both narratives advocate humility. Humility before our fellow humans means accepting that we cannot enforce a universal truth on everyone. Humility before God requires us to accept that despite the chaos of the world, there is a universal truth that lies beyond human comprehension. In a world where countless voices clamor for attention, it is reassuring to remember that, even if it is beyond our grasp, there does exist a singular truth that unites us all.

Suggested Reading

A Modern Exodus

BY SONIA SCHACHTER The biblical book of Exodus is a well known story. It recounts the story of the Jews brought out of Egypt with the mighty hand of God,…

David and Goliath: A Deeper Look at the Underdog Story

BY GILA GRAUER In Sefer Shmuel, the book of Samuel, the story of David and Goliath tells the narrative of a young shepherd who defeats a giant warrior. Goliath is…

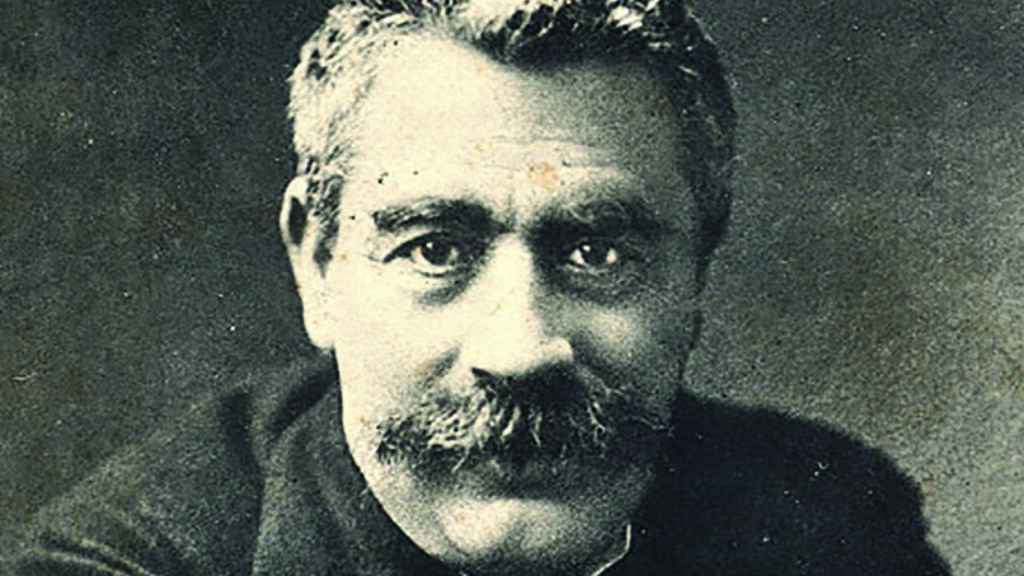

I.L. Peretz’s Legacy: Challenging Jewish Passivity

BY BENJIE KATZ If any American has heard of the shtetl, the little market towns where a significant portion of Jews in Eastern Europe lived until the early twentieth century,…

Lessons from Under Devorah’s Date Tree

BY RITA SETTON If one were to choose Judaism’s most prominent or distinguished teacher, Moshe Rabbeinu or Avraham Avinu instantly come to mind—and with good reason. During their lives, they…