My Tutors’ Joy and the Joys of Tutoring: The Power of Non-Traditional Learning Methods

BY YARDENA FRANKLIN

Since before I can remember, I have been going to shul with my dad, my very first tutor. Listening to the davening and leyning long before I could understand what they meant, I was a witness to my father and community’s delight in daily prayer and communication with God. Officially, my informal Jewish education started at the age of five, when I started attending public school. My father taught me Chumash, reading the English translation of the Stone Artscroll Chumash with me every week. We would meander through the weekly parsha, stopping frequently to answer my barrage of questions. From the minutiae of Temple sacrifices to the Binding of Isaac and biblical relationships, I investigated and analyzed everything with my father’s hand in mine.

As I grew older, the teachers changed; now my tutors ranged from a Yeshivat Drisha Kollel fellow, to a Gemara teacher, to my grandfather, a Modern Orthodox Rabbi. Their firsthand fascination and joy kept me enchanted, unable to tear my eyes and heart away. I learned with my tutors outside of school, excited to explore all I could about the world of the Torah and the Talmud. My Jewish learning was purely delightful, driven almost exclusively by my own motivation.

These teachers encouraged me to learn and develop my own relationship with Torah and God. As we covered new ground in the Gemara, I built up my weakest skills, breaking my teeth over Aggadah, a collection of stories and folklore with challenging Hebrew and complex narrative structures. I learned the structure of a Gemara, equipped with the tools to pursue knowledge on my own. My chavrutas, study partners, were models, showing me a framework I could apply independently.

As the former St. John’s tutor Eva Brann alludes to in her quote, “Teaching is above all the controlled public display of delight. A teacher is a lover-in-chief prepared not only to be observed in the activity of love but to beckon students into it,” in my experience, good teachers are not only experts in their fields, but model their passion for their students to witness and be inspired from. It is simply not enough to disseminate information to students. In order for students to truly internalize their lessons, teachers must elicit active participation and care from their students.

This is why I believe tutoring and one-on-one learning most closely illustrate Eva Brann’s description of teachers as the “lover-in-chief.” In traditional classroom settings, with one teacher in front of a class of over twenty students, it is nearly impossible to give each student the time they deserve. This is particularly true in modern society, where many teachers are strained, often overworked and underpaid. It is idealistic to believe that every student is receiving the proper level of care at the proper pace in this setting. With the current state of traditional education, in order to effectively “beckon students into it,” we should turn to alternate forms of education, such as one-on-one tutoring or small group instruction. With these methods, teachers have the space to develop personal relationships with students, and convey their passion in a way that can more effectively influence their students. It is simply not enough to be a “lover-in-chief” for its own sake; it is critical to share knowledge so that it has a meaningful influence on students’ lives.

When working one-on-one, there is a unique opportunity to tailor education to students’ interests and needs. As the Chinese proverb states, “Give a man a fish, he’ll eat for a day; teach a man to fish, and he’ll eat for a lifetime.” So too in teaching, the content itself is nowhere near as meaningful as building healthy learning habits. In building such habits, teachers help their students become self-motivated and self-sufficient.

Moreover, Brann’s quote necessitates the question: “What comes next?” As students, to whom do we look once we have been beckoned by the calls of delight in learning? Now, we are hooked, ready to explore on our own. My conception of the purest teacher is one who longs for a day when their students do not need them, for when the students have the knowledge, motivation, and skills needed to healthily explore on their own. Similarly, I believe teaching is always intended to be finite.

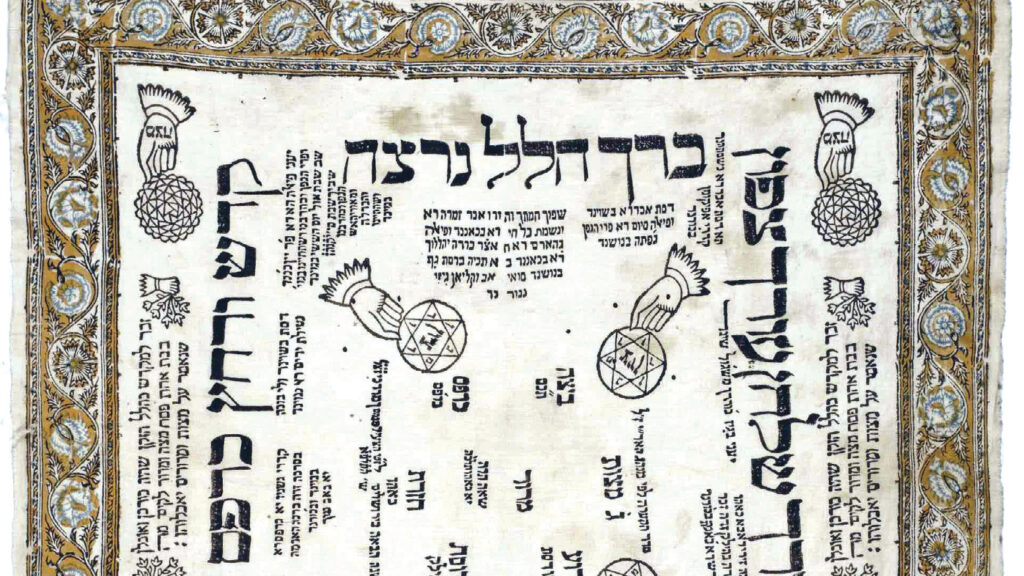

In the Jewish tradition, the concept of generational knowledge is the foundation of the Oral Torah and the structure of makhloket, debate, within the Talmud. In order to propose an alternate interpretation of an authoritative text, or reject another Rabbi’s claim, one must cite authoritative texts or opinions held by previous generations of rabbinic leaders. These makhlokets are based on the authority of previous leaders, while leaving room for new, independent interpretation in later generations.

This framework of argumentation, which can be studied and learned, means the Jewish canon and the official halakhic practices of all times are living and breathing, continually updated and reckoned with. This living practice gives people space to be inspired. From key figures like Rabbi Akiva, who learned Torah for the first time at age 40 before becoming a Talmud chakham, to the relationship between students and teachers as laid out in the Talmud, learning is student-motivated and teacher-driven.

Judaism provides a blueprint for a healthy relationship with academic authority, one which intentionally challenges, but ultimately accepts and encourages wisdom. The Gemara in Rosh Hashanah 25a provides a perfect representation of this phenomenon. Discussing a disagreement as to the date of the beginning of the new month:

“When Rabbi Yehoshua heard that even Rabbi Dosa ben Horkinas maintained that they must submit to Rabban Gamliel’s decision, he took his staff and his money in his hand, and went to Yavne to Rabban Gamliel on the day on which Yom Kippur occurred according to his own calculation. Upon seeing him, Rabban Gamliel stood up and kissed him on his head. He said to him: ‘Come in peace, my teacher and my student. You are my teacher in wisdom, as Rabbi Yehoshua was wiser than anyone else in his generation, and you are my student, as you accepted my statement, despite your disagreement.’”

In this relationship, despite hearing the date calculations of his Rabbi, Rabban Gamliel, Rabbi Yehoshua not only disagreed with his teacher, but had matured enough to both recognize his own position and defer to authority.

For Brann, there are two parts to teaching, the passion for one’s field, and the ability to communicate that passion to one’s students in a way that compels them to continue to learn. In my own life, I’ve also found it just as important to ask, “What next?”

Suggested Reading

Shining Our Light Unto the Nations Through Jewish Teachings

BY ADIN LINDEN Jewish history is rife with enemies, from the Egyptians to the descendants of Amalek, a lineage that is seen as the greatest enemy of the Jews and…

Between Separating Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in Others

BY YAEL BURGESS EISENBERG When a gentile came before Hillel and said he would convert to Judaism if Hillel could teach him the entire Torah while standing on one foot,…

Fortifying the “Torah” in Torah u-madda: A Plea to Modern Orthodox Day Schools

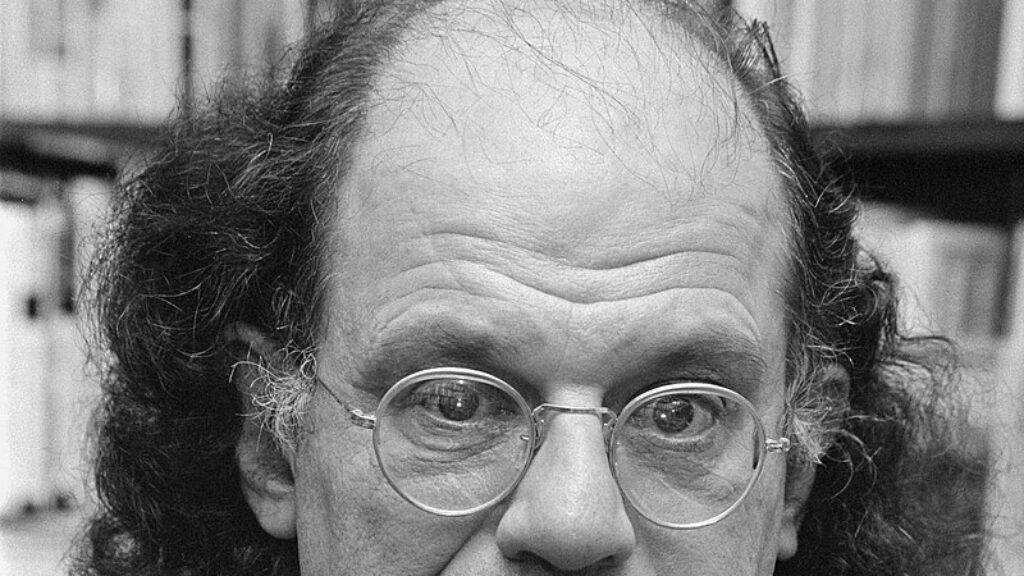

In a deep look at his background and motivations, the picture of Jewish writer Allen Ginsberg becomes more clear to the observer. His difficult past and masterful mix of secular, religious, and kabbalistic, as well as various other, themes in his work came to a head in his poem "Kaddish", written to be an elegy for his mother.

Learning as Creation: The Power of Jewish Education

BY ZACHARY KROHN It is no secret that education is one of the highest values of Judaism, and one can give many reasons for why that is the case. Education…