The Identity Crisis of Robert Moses

Throughout the twentieth century, New York was defined by some of the same forces that shaped other major American cities: the Great Depression, waves of immigration, the World Wars, and the post-war boom. However, New York has the unique distinction of being carved via the behind-the-scenes machinations of one man: Parks Commissioner Robert Moses.

Moses looms over the landscape of New York City. Born in Connecticut in 1888 to German-Jewish parents, Moses rose to power in the 1920s and, over the course of a 50-year career in public works, effectively created New York’s major infrastructure. His accomplishments include the construction of the city’s key highways, bridges, stadiums and parks. In many ways, Moses fundamentally transformed New York. Despite his successes, however, evidence suggests that Robert Moses is not quite the valiant giant of civil engineering history has made him out to be. In his 1974 biography The Power Broker, historian Robert Caro masterfully paints Moses as an enigmatic tyrant who dominated the city’s development for over sixty years.

In Caro’s telling, Moses was fueled by a tyrannical streak rare in the history of his coreligionists. Indeed, Caro describes Moses’s projects as “the means of attaining more and more power.” Caro’s assessment of the nuances of Moses’s career emphasizes the tensions surrounding Moses’s Jewish identity, which Caro explains affected his capacity to serve as a city planner. In addition, the prejudices Moses faced throughout his academic and professional experiences drove him to cement his grip on public works, rather than allow his Jewish identity to get in the way of his aspirations. The story of Robert Moses is emblematic of an American-Jewish success story, yet it is also cautionary, illustrating the pitfalls of power through the life of a deeply flawed man.

Moses’s time at Yale University (1905-09) was a defining period in terms of his relationship to his Jewish faith. Throughout an academically successful college career, Moses displayed both brilliance and determination, yet he struggled to find a foothold in the Episcopalian world of Yale, as fraternities which conferred campus social status would not admit Jews. In response, Moses began the process of creating what Caro calls “a world of his own… in which, in collegiate terms, he [had] power and influence.” This sphere of influence included a dedicated group of friends, both Jewish and otherwise, who greatly admired Moses and assisted him in furthering his social stature within Yale. In his professional life, this became a trademark; he refined his ability to attain positions of power through relationships. Yale marked the first time Moses’s religion and quest for power conflicted. Yet, as we will see, for Moses, power was everything.

Moses’s relationship with Judaism became more tenuous during his battles with Tammany Hall’s corrupt political machine. Tammany Hall, the largely Irish Catholic political organization dominating the city’s government, orchestrated the placement of its members into positions of power and strove to keep Jews like Moses out. For Moses, this was like the Yale fraternities all over again. One such instance occurred during the tenure of Tammany Mayor Red Mike Hylan, in which “[n]on-Tammany employees were forced out of their jobs by pay cuts and humiliating assignments.” In this case ethnicity was a huge disadvantage; Moses once again sustained a loss in his quest for recognition and was once again maligned because of his affiliation with Judaism.

As Moses’s career progressed, his aspirations were continually thwarted due to his Jewish identity. Therefore, Moses seized the first opportunity to renounce his community and follow the path of power. His chance came during the 1934 New York gubernatorial election, in which Moses ran against the Jewish Herbert Lehman, a budding star in New York’s political scene. In his campaign, Moses “insisted he was not Jewish,” even going so far as to “[make] disparaging remarks about characteristics he felt exemplified Jews.” Even though Moses’s renunciation of Judaism failed to help him win the gubernatorial election, he did not re-embrace his boyhood religion.

Moses continued his ascent, gaining control of government commission after government commission until his power was comparable to that of an autocrat, rather than a mere Parks Commissioner. He held up to 12 official titles simultaneously. At some point, Moses had not only taken control of a network of legislators who heeded his every beck and call, but he also utilized this position to reshape his power as he saw fit. His grasp on New York politics was so extensive that even Moses’s greatest opponents, such as then-governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, were powerless to stop him. This staggering authority had followed his tremendous renunciation of his faith, steering Moses to further sever his ties with the Jewish community of New York.

Moses’s ultimate rejection of Jewish faith began strictly due to his own ambition. His ambition was so intense, and his means at times so underhanded, as to be Machiavellian. Ironically, if Moses had rejected Judaism without publicly embracing another religion, he would have acted contrary to Machiavelli’s advice in the Prince: “There is nothing more important than appearing to be religious.” If we think Moses had Machiavelli’s advice in mind––either from his reading or by recreating the old philosopher’s advice––it therefore makes sense that Moses eventually converted to Episcopalian Christianity. Given his past failures in Yale social circles, it is not difficult to conceptualize the underlying purpose of this conversion, wherein Moses would finally belong with his collegiate antagonists. It is unlikely that Moses spiritually embraced his new faith, and his conversion was merely intended to embellish his political image.

In his chronicling of Moses’s rabid pursuit of power, Robert Caro does not miss a beat. Caro paints Moses as a man who could have been truly great; a selfish civil servant who in his pursuit of control lost sight of his mission to do good for the general populace. Underscoring this notion, Caro delves deep into the psyche of Moses, expressing the implications of absolute power when wielded by an autocratic figure. In this portrayal of Moses’s hubris, The Power Broker serves as a cautionary tale to talented young people everywhere as they enter adulthood, admonishing those who would pursue the path of power in the name of personal attainment.

Suggested Reading

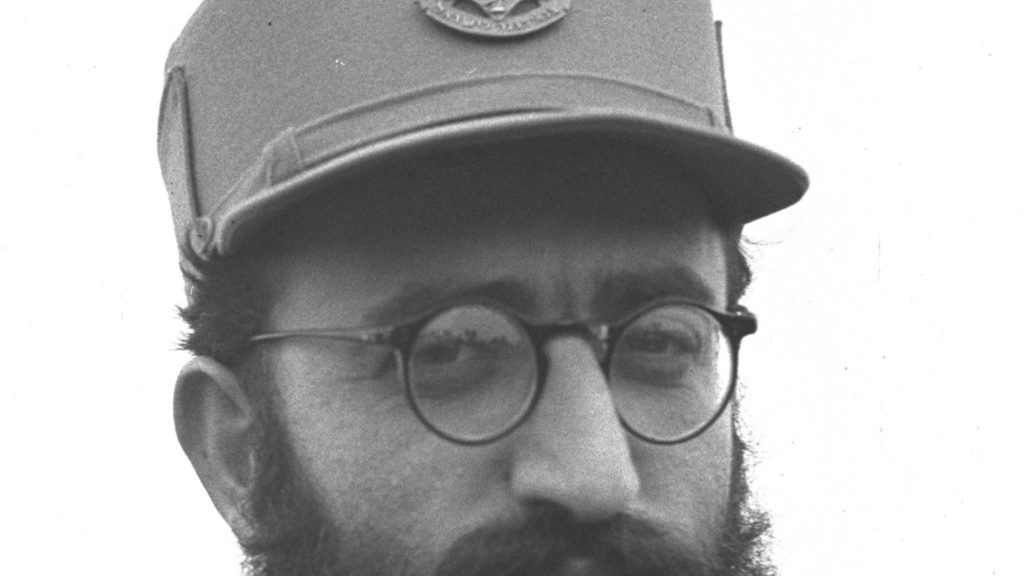

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

A Jewish Perspective of Longing

BY SAMUEL FIELDS Since the calamity of October 7, there has been Jewish achdut, unity, around the world. Such achdut requires respect for each other and keeping our eyes on…

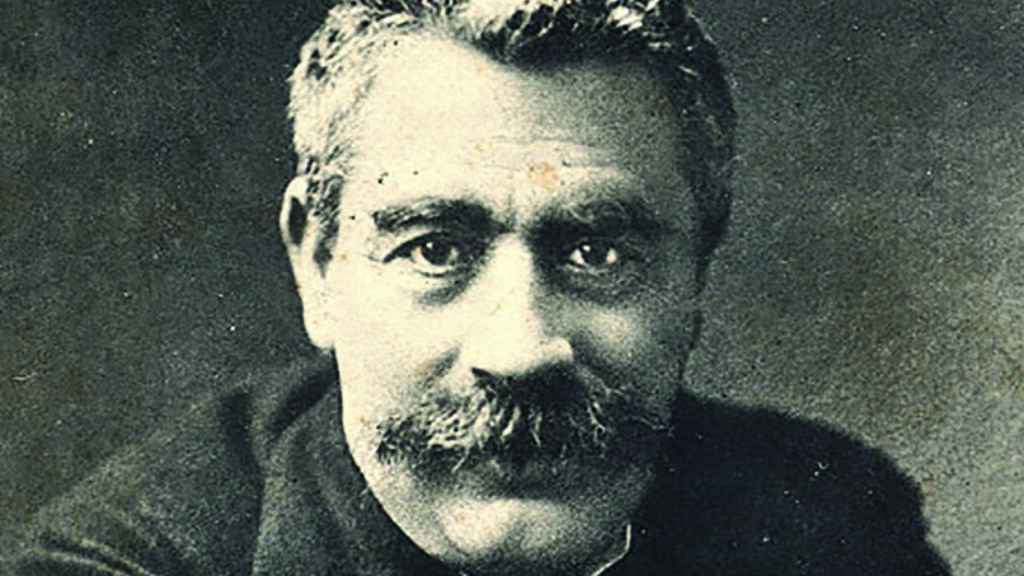

I.L. Peretz’s Legacy: Challenging Jewish Passivity

BY BENJIE KATZ If any American has heard of the shtetl, the little market towns where a significant portion of Jews in Eastern Europe lived until the early twentieth century,…

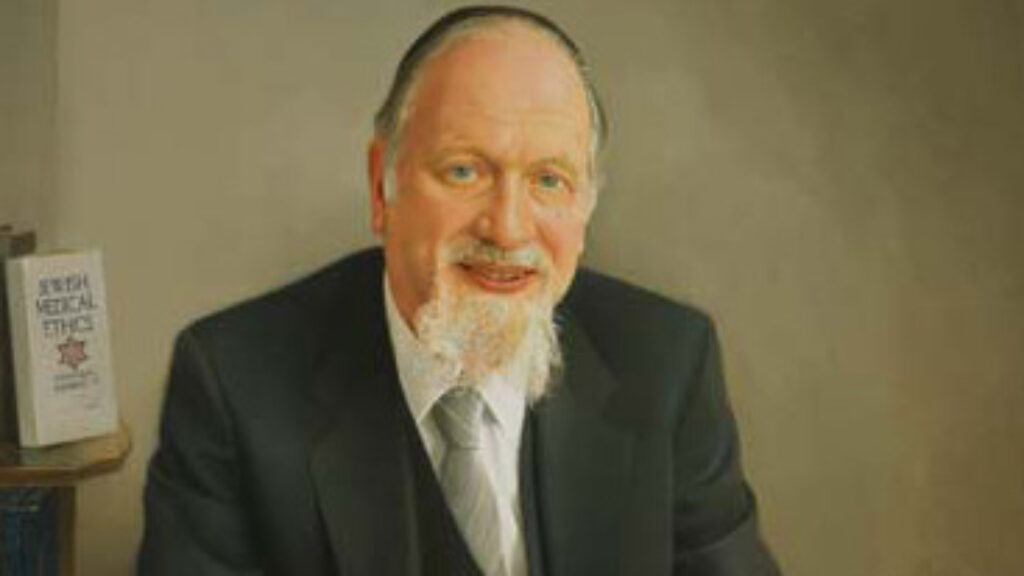

“If Only My People…” Zionism in My Life

BY GIDEON ROSEN “And I will give you as a light for the nations so My salvation will reach the edge of the earth” (Isaiah 49:6) In his book, “If…