The Dichotomy of Modern Culture: A Nietzschean Perspective on Aesthetic Oscillations

BY RACHAEL KOPYLOV

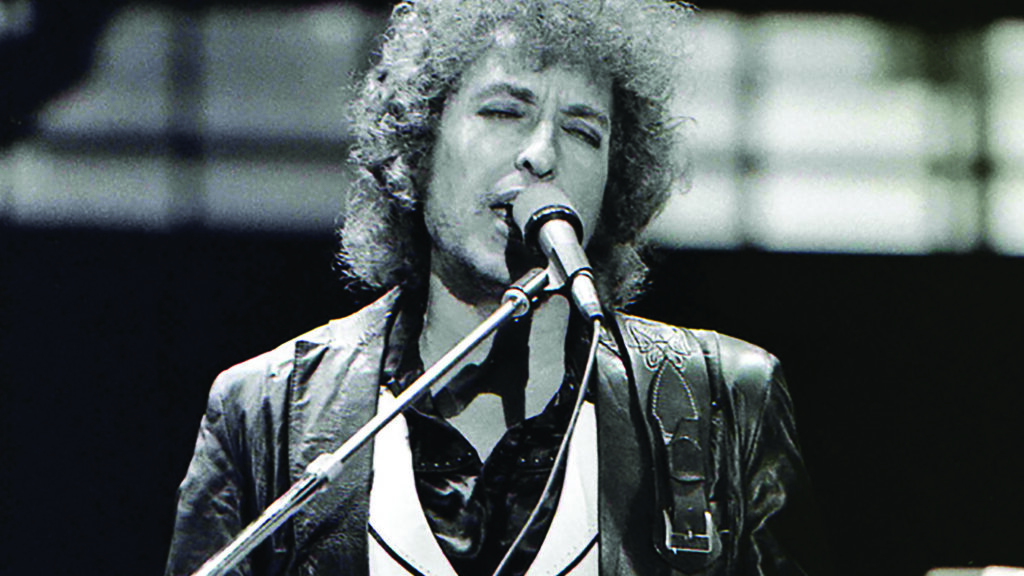

Art permeates every aspect of our lives, from visual expression to music and fashion, it shapes and evolves alongside us as it reflects the human experience. The clothes we see on the runway and subsequently purchase, the graffiti we see on the streets, and the music we listen to on our way to work every morning are a reflection of society’s psyche, showcasing the values and qualities of various communities. Today, we find ourselves in an era where society is relentlessly shifting between various artistic extremes.

Recent months have vividly illustrated this oscillation. This summer saw the rise of “Brat Summer,” an aesthetic movement characterized by unapologetic boldness and a carefree attitude. The rejection of organization and convention gave way just weeks later to “Demure Fall,” which is the opposite of “Brat Summer,” with its simplicity, calm, and quiet luxury. “Demure Fall” and its rapid rise to popularity can be seen as a reaction to the overstimulation of summer trends. After weeks of disorder and boundary-pushing, “Demure Fall” promised a return to order and spoke to the universal desire for balance, serving as a collective reset and return to structure and restraint.

Such fluctuations in trends are not new. Numerous artistic movements have emerged as a reaction to social revolutions, geopolitical turmoil, or other, opposite, creative trends. Neoclassicism, a late eighteenth century fashion trend characterized by soft tones, lightweight fabrics, and classical motifs, was seen as a response to both the French Revolution, a time of immense political and societal turmoil, and the Rococo period, a clashing eighteenth century style that focused on asymmetry, ornate decoration, and frilly details.

Similarly, cultural trends in the 1930s, mostly influenced by the Great Depression, emphasized modesty and conservatism, a striking divergence from the dazzling “flapper girl” style of the Roaring Twenties. These drastic aesthetic shifts are not an anomaly; they mirror the inherent human desire for balance, with each movement supplying what the previous had lacked.

Cultural movements do not exist in isolation; rather, they fuel the constant pendulum swing of aesthetics between chaos and order, maximalism and minimalism, rebellion and structure. This fluctuation between extremes is far from a contemporary cultural phenomenon; rather, it reflects a deeper tension that has shaped artistic expression for centuries. In his debut work, The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche explores humanity’s inclination towards dichotomy through the lens of ancient Greek art. He does so through dissecting two opposing forces—Apollo and Dionysus—which each play an indispensable role in art and culture.

Apollo is the Greek god of the sun, music, poetry, and healing. He symbolizes harmony, order, and individuality. Drawing from the ideas of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, Nietzsche introduces the concept of principium individuationis, which, translated from Latin, means the principle of individuation. This idea is central to Nietzsche’s understanding of Apollonian art and existence. It refers to the processes that enable individuality, or the boundaries that distinguish one person from the chaotic, amorphous whole. Schopenhauer’s definition of principium individuationis organizes life into distinct spaces, times, and events, creating the illusion of separation and individuality. He argues that the illusion of principium individuationis is what protects humanity from the “Will,” which is the source of all suffering. According to Schopenhauer, art—especially music—provides an escape from the ordinary, painful existence caused by the “Will.”

While Nietzsche agrees that principium individuationis makes us feel separate from others, he doesn’t see it as something humanity needs to escape. Instead, he believes it’s an important part of how we create and experience the world. Nietzsche adds that Apollonian art is the cultural and artistic expression of principium individuationis. Apollonian art seeks to bring structure to the chaotic nature of existence, producing an illusion of stability, uniqueness, and elegance. However, Nietzsche contends that it is only an illusion, because beneath the appearance of order lies the ever-present chaotic and primal forces of Dionysian existence.

As the Greek god of wine, madness, ecstasy, and savagery, Dionysus stands in stark contrast to Apollo. He is a paradox, representing celebration and freedom, but also violence and suffering. Nietzsche connects Dionysus to the concept of “primordial unity,” a state where all boundaries and distinctions between individuals dissolve. Much like Dionysus himself, primordial unity is inherently paradoxical, simultaneously merging pleasure with pain, and beauty with savagery. The Dionysian festivals in ancient Athens perfectly illustrated this, because they were gatherings at which women, slaves, and children participated alongside Athenian men, which was a temporary break in strict societal norms. All of Athens came together during these gatherings, often intoxicated, exposing the hidden primal chaos beneath the surface of orderly society.

Nietzsche uses primordial unity to describe life’s true depth, which lies beneath the structure of principium individuationis. While this unity can be overwhelming, it also reveals an essential truth: life is paradoxical, capable of holding two opposing forces—chaos and creation, joy and pain—in coexistence. For Nietzsche, primordial unity and the Dionysian way of life are central to art, and indispensable to art in its greatest form. Without acknowledging this deeper, more tumultuous side of life, art would become mere decoration, lacking substance and meaning.

Although Nietzsche expresses a strong preference for Dionysian art in The Birth of Tragedy, he argues that true art requires a balance between both Dionysian and Apollonian forces. He asserts that since the time of Socrates and the playwright Euripedes, society has increasingly favored the Apollonian principles of rationality and individuality, at the expense of the Dionysian. He attributes this shift to the death of art. The raw emotion of tragedy, which Nietzsche viewed as the highest form of Greek art, was diminished by the Socratic emphasis on reason that Euripides introduced to theater. Before the influence of Socrates and Euripedes, Nietzsche saw Greek tragedy as the pinnacle of art because it balanced Apollonian and Dionysian elements. This balance allowed the paradox of existence to be expressed in a vivid, nearly tangible way, which enabled humanity to experience the beauty and order of life as well as the suffering and confusion that inevitably accompany it.

In the final chapters of The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche connects the fall of Greek tragedy to the rise of rationalism in German culture, urging a return to the primordial unity and Dionysian principles in art that preserve the delicate balance crucial to its expression; however, in the modern world, Nietzsche’s pleas go largely unheard. Today, he would likely be disappointed by the disparity between the different artistic movements like “Brat Summer,” which embodies Dionysian chaos and freedom, and “Demure Fall,” which upholds the Apollonian ideals of beauty, structure, and principium individuationis. This constant back-and-forth is reflective of society’s struggle to find balance, shifting back and forth between extremes in search of equilibrium. Contemporary artists would be wise to revisit Nietzsche’s teachings and create works of art that provide the balance that our society so desperately desires, fostering cultural movements capable of redefining and elevating human potential.

Suggested Reading

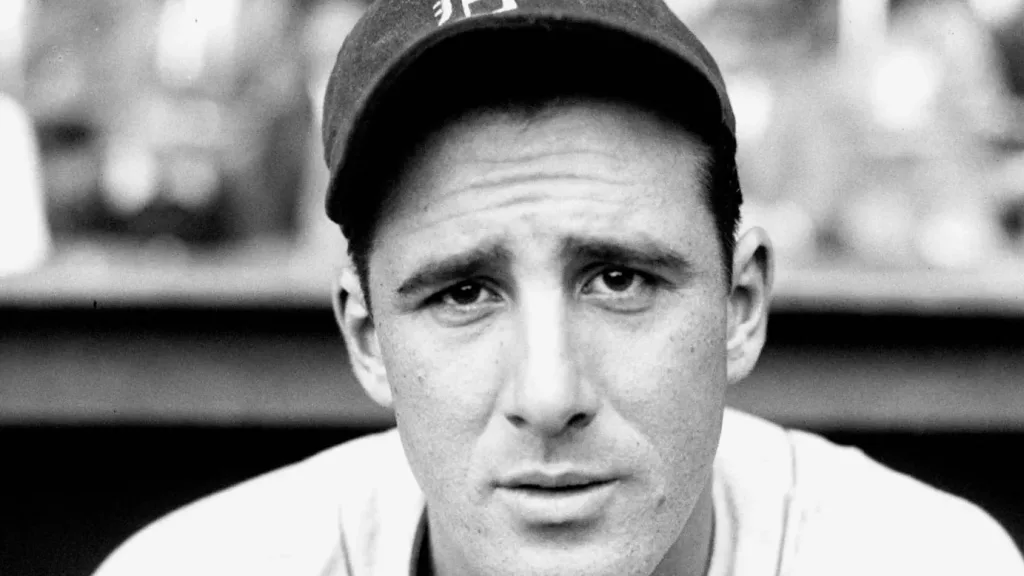

An American Jewish Folk Hero

A striking fact about modern Zionism is that its founder, Theodor Herzl, dedicated his life to Jewish statehood despite originally caring little for Jewishness. At one point, he even advocated…

The “Neighborhood Bully” Returns

BY EMUNA NAIDITCH What happens in the Jewish state affects each and every Jew. As poet Yehuda Halevi famously said, “My heart is in the east, but I am at…

The Importance of the Arts

BY RAFI UNGER What distinguishes humans from animals is our capacity for creativity and generating new ideas. In essence, the unique creativity of humans separates us from other creatures. Unfortunately,…

The Importance of Extracurriculars

Extra curriculars have long been proven to not only aid students in having safe and healthy hobbies, but also in making sure children are ready to become independent adults. The importance of pursuing potential and growing into your own person is both a Jewish value and vital for the future of the Jewish people.