Einstein’s Recalculation of Zionism

Walter Isaacson’s 2007 biography of Albert Einstein—Einstein, His Life and Universe—provides a compelling and detailed account of the scientist’s life as well as insights into his scientific and political views. Einstein is best known to the general public for his scientific accomplishments, but his political attitudes are notable. His New Jersey office featured paintings of both Sir Isaac Newton, representing science, and Mahatma Gandhi, representing equality and human rights. In Isaacson’s words, “his passions were as much political as they were scientific.” Indeed, the two were intimately linked in Einstein’s life.

As a child growing up in Germany in the 1880s, Einstein challenged facts and authority, a quality that is also evident in his lifelong willingness to question prevailing scientific theories (the most notable example of which is the way he developed his theory of relativity). One can discern a similar willingness by Einstein to challenge views in the political domain: he opposed authoritarianism in both its communist and fascist varieties. One way Einstein initially sought to oppose authoritarianism was by adopting pacifism; in 1895, at the age of 17, he renounced his German citizenship and moved to Switzerland to attend college and thus avoid having to serve in the German military. In this way, he attempted to model an alternative to the violence.

However, after the Nazis gained power in Germany in the 1930s, Einstein promoted fighting in an army. Einstein’s shifting approach to countering authoritarianism similarly evidenced a scientific approach. His original hypothesis of warfare was that it should be avoided at all costs. However, Einstein’s view changed when he realized that force was required to stop the Nazis. Thus, Einstein, as a good scientist, altered his political views when the data on the ground countered his assumptions.

Einstein’s evolving attitudes toward Zionism similarly show the influence of his scientific approach on his political views. As a pacifist and opponent of nationalism, Einstein did not wholly embrace the idea of a Jewish state, at least at first. He had a difficult time connecting to the idea of Zionism because he had a difficult time connecting to God. While Einstein had difficulty believing in an all-powerful God who interferes with people’s lives, he nevertheless, still believed in God’s creation of the world. Einstein felt that God’s creation of the world included predetermining all subsequent events. Einstein’s belief in a deterministic world challenged his ability to connect to God, leading him to abandon Jewish ritual beliefs shortly after his bar mitzvah. His attachment to the idea of a Jewish state diminished alongside his attachment to Jewish practices and beliefs. While he still wished for a political solution to the Jewish problem that might involve moving Jews to the British Mandate of Palestine, he did not believe that Jews should have their own full-fledged state.

With his goal of a Jewish presence in the Palestinian Mandate in mind, Einstein was an early player in the Zionist movement and key fundraiser. Einstein, along with future president of Israel Chaim Weitzman, traveled to America to advocate for the establishment of the State of Israel and Hebrew University. The trip was Einstein’s first trip to America, where he was greeted as a megastar. He was able to use his media attention to speak on behalf of his beliefs, including his pacifist ideals. However, as the years went by, Einstein started believing in a Jewish presence in the Middle East less and less; he felt that the Jews in Israel were persecuting the Arabs, and that Zionism was just a misguided form of Jewish nationalism.

In the face of the evils presented by the Nazis and Axis powers, though, Einstein reassessed his pacifist beliefs. He helped to develop an atomic bomb to be used against the Axis powers. With the Nazi atrocities against the Jews at the front of his mind, he also reassessed his Zionist beliefs and once again began to support the Jewish State.

Anti-Semitism’s effect on science was the primary cause of Einstein’s reassessment of his pacifist beliefs. While he knew he was Jewish, his Judaism was just one part of his identity. With the emergence of Nazism, however, Einstein’s “Jewishness” became magnified in others’ eyes. This made life challenging for him, as more scientists started denying the idea of relativity because of its “Jewish” origin. Many Jewish scientists were kicked out of Nazi Germany, and Einstein himself received many threats. The more hate he received, the more he connected with his Jewish brethren’s struggles. He also stopped believing in his own idea of pacifism.

Germany led the world in terms of scientific achievements at the time, many of which were due to prestigious Jewish scientists. Many of his peers were less fortunate than Einstein was and did not have countries that would welcome them or available jobs that they could quickly fall back on. With his beloved practice of science under attack, Einstein was finally forced to confront the truth that at times one must fight fire with fire.

When Einstein witnessed the vast number of Jewish deaths resulting from Jewish powerlessness in World War II, he decided to support the State of Israel again. Einstein came to believe that even if the partition plan were to result in the infringement of Arab rights, this scenario would still result in a more equitable solution for both Jews and Arabs. Einstein was even offered the position of second president of the Israeli government. Apparently Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was relieved that Einstein did not accept this offer: “Tell me what to do if he says yes!” He joked to his assistant. “I’ve had to offer the post to him because it is impossible not to. But if he accepts, we are in trouble.”

These and other shifts in Einstein’s political positions demonstrate how his scientific views influenced his political ones. When he was proven wrong, he was willing to revise his “hypotheses” about the ways in which political systems ought to work, rather than stubbornly cling to his previous ideas. This willingness to change his mind also demonstrates his humility—an important characteristic in a scientist.

Suggested Reading

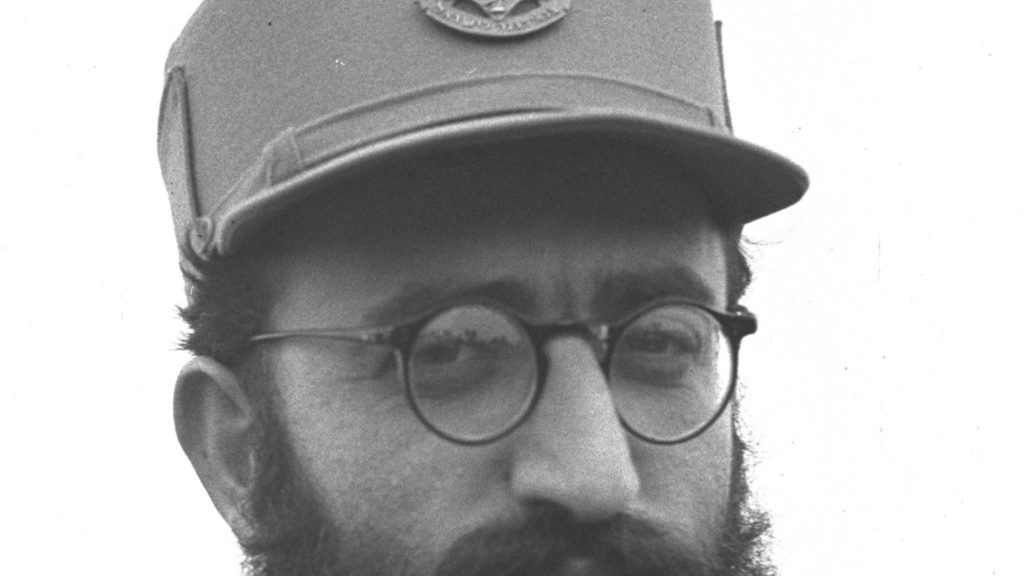

The First Religious Paratrooper

Rabbi Shlomo Goren’s autobiography, With Might and Strength, tells the story of a precocious rabbinical student who decided to join the Israeli army and eventually became Chief Rabbi of Israel. By…

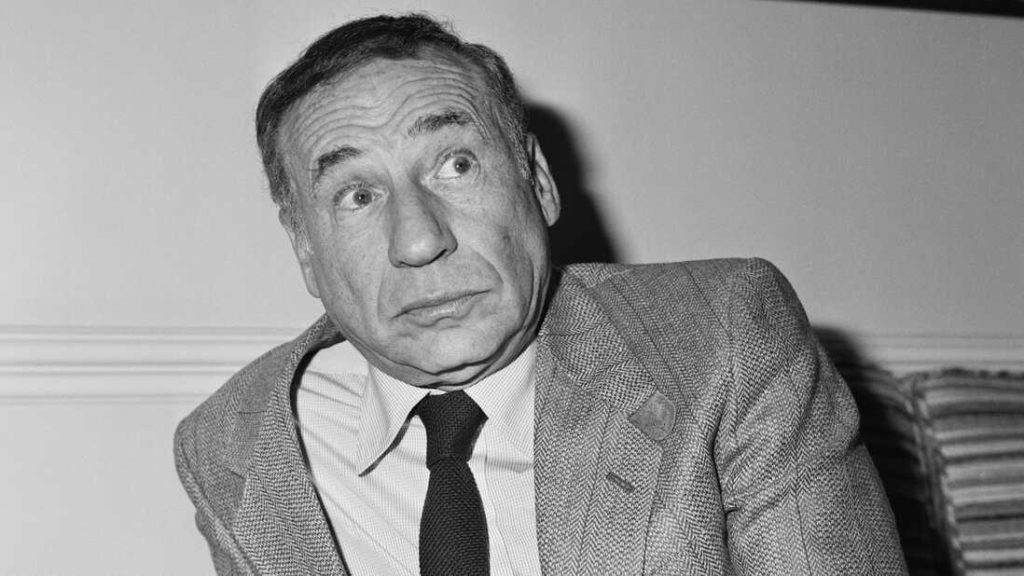

All About Mel

In an iconic moment of the 1967 film The Producers, scantily clad dancers dressed as Nazi sturmtruppen move into swastika formation and slowly rotate, surrounded by Third Reich banners and singers extolling the…

The Six Elements of Resilience Inherent in the Jewish Tradition

BY RAANAN VANDERWALDE There is no denying that Jews are resilient. Judaism is one of the oldest religions in the world. For over 3,000 years, Jews have been persecuted, killed,…

The Out-of-Town Jew

BY MORIAH SCHRANZ Growing up, I loved the fact that I was Jewish. Living in an area with few Jews, this was my unique trait. It was my go-to fun…